1. The European Stablecoin market is underdeveloped. So far, there are just 17 Stablecoins licensed as Electronic Money Tokens (EMTs) under the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) of the European Union (EU), worth a total of US$600-700 million. This compares with several hundred US dollar equivalents worth more than US$300 billion.

2. The imbalance between the US dollar and euro Stablecoin markets reflects the longstanding dominance of the US dollar in all forms of commercial activity globally. Companies and individuals in jurisdictions where capital controls or volatile domestic currencies obstruct conventional means of access to US dollars were the original customers of Stablecoins and remain important users. US dollar Stablecoins also dominate in the cryptocurrency markets, where all the currency pairs refer to US dollars and traders use the US dollar as their base currency (because of its ready availability and relatively high liquidity). Holders of Stablecoins on-chain can even obtain yields as high as 12 per cent on their holdings via decentralised lending protocols such as Aave, Compound, Morpho and Metamask. Yields on euro Stablecoins, where demand is lower, are as little as a third or a quarter of the yield on US dollar Stablecoins. This further depresses demand for euro Stablecoins from retail investors. A further factor is the absence, unlike in the United States, of a single European fiscal policy, which creates country risk in euro government debt. This fragments the quality of the government bills and bonds that euro-denominated Stablecoin issuers need to hold as reserves (though it can also be argued that a euro portfolio of Stablecoin reserves is more diverse than its US dollar equivalent). In the long term, this problem might be solved by Bitcoin (or some technologically superior cryptocurrency) emerging as a stateless, universally acceptable reserve asset, perhaps for central banks as well as Stablecoin issuers.

3. But the real barrier to Stablecoins growing in Europe is the banks. Stablecoins will not take off in Europe until the banks embrace them, because the banks control access to the corporate treasurers that hold and use cash at scale and that would benefit most from using Stablecoins. And, at present, banks are reluctant to endorse Stablecoins because they profit mightily from a status quo global payments industry that generates, according to McKinsey, US$2.5 trillion in revenue from US$2 quadrillion in payments. European banks fear that, if they offered their corporate clients a convenient way to convert euros on deposit into Stablecoins, they would crush their own margins. Banks also intimidate corporates, which are reluctant to open digital wallets and use Stablecoins because their banking relationships are useful to them for other reasons.

4. The growth of euro Stablecoins in Europe is further constrained by the fact that existing payments systems in the euro area are competitive. The EU Instant Payments Regulation (IPR), which mandates all banks offering euro payments to provide instant payment by October 2025 (within the eurozone) and July 2027 (outside the eurozone), is universalising access to Single European Payments Area (SEPA) Instant Credit Transfers (SCT Inst) 24/7. SEPA also means the cost of making payments across national borders within Europe is nugatory by comparison with the equivalent costs in Asia or North America. SEPA payments are fast as well. This makes euro Stablecoins relatively less attractive as a payment method in Europe. That said, the benefits of SEPA are not available once payments must be made to counterparts beyond Europe. Cross-border payments outside Europe remain expensive, slow, hard to access and opaque. In principle, wallet-to wallet transfers of euro Stablecoins would be highly competitive outside Europe, but regulated banks would still have to operate them in compliance with Anti Money Laundering (AML), Countering the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) and sanctions screening regulations.

5. Tokenised money market funds denominated in euro, accessible via euro Stablecoins, are already helping the euro Stablecoin market to grow. These appeal to institutional investors in a way that decentralised lending protocols do not, but tokenised money market funds remain digital twins rather than digital natives, attenuating the cost savings and yield pick-up. Indeed, holders must pay off-ramping as well as on-ramping fees to banks to buy and sell tokenised money market funds, and act before the daily cut-off deadline as well. The cost-savings, gains in yield and operational convenience need to be larger if tokenised money market funds are to scale. Programmable money issued and exchangeable on-chain in native form, which calculate yield by the second or the minute, can deliver large enough benefits to accelerate the use of euro Stablecoins because the transaction costs of moving and servicing digital money repeatedly are trivial.

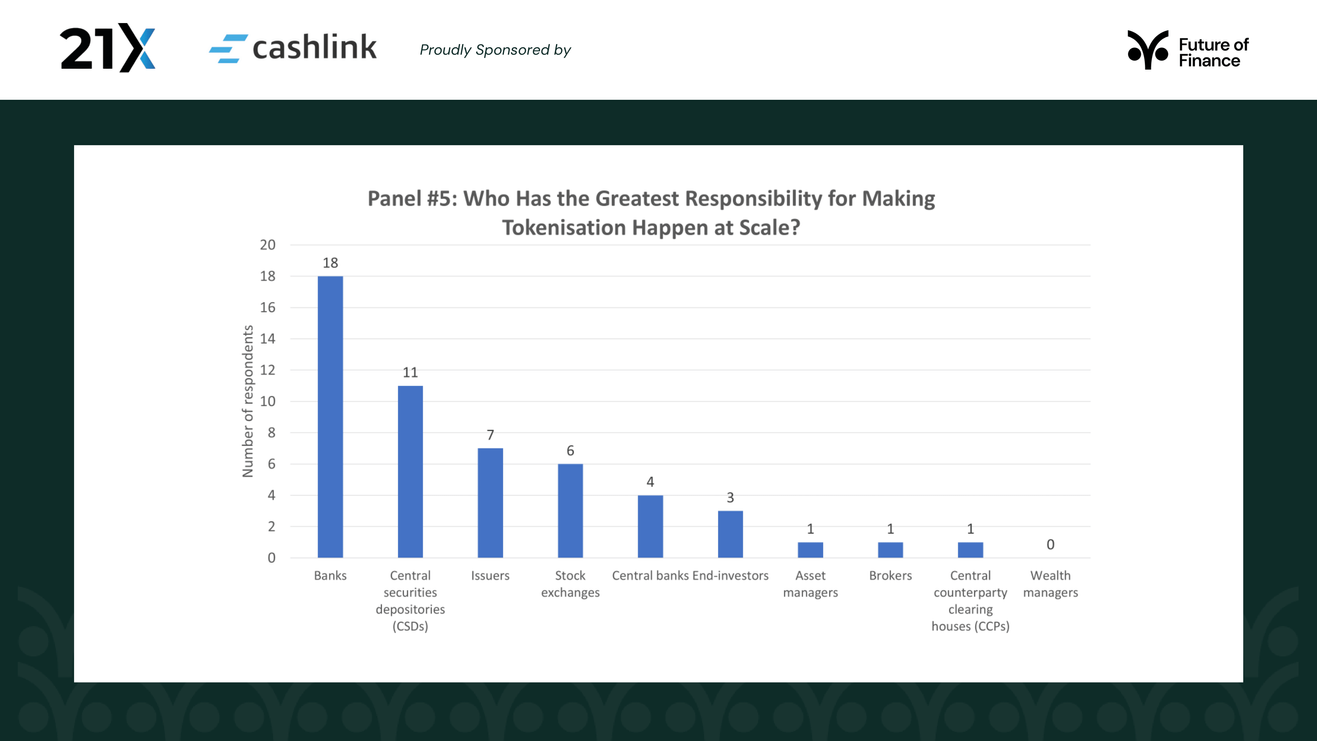

6. Another use-case capable of breaking the institutional bias against Stablecoins in Europe is the development of tokenised structured products and tokenised securities markets, in which euro Stablecoins would enable traders and investors to avoid the costs of coming off-chain to access cash. Central securities depositories (CSDs), as guardians of the integrity of issuances, can make securities available in digitally native form. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has recognised that the EU Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) Pilot Regime, a regulatory sandbox that allows market participants to test the trading and settlement of tokenised securities, is not working well because the thresholds are too low and the range of permissible products is too narrow. The Pilot Regime is being revised to lift the thresholds, widen eligible products to include privately managed assets and complex structured products, and broaden the range of settlement assets. However, the changes might not be effective until 2028. There is a risk that the EU squanders the lead created by MiCAR, the Pilot Regime and the ECB trials and experiments, and is overtaken by the United States, where the deregulatory approach of the Trump administration has killed the idea of settlement in central bank money and galvanised the banks (including some banks in Europe) into developing digital asset strategies.