For true tokenisation to triumph a public initiative is needed

- May 8, 2024

- 36 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

The tokenisation of securities and funds is the blockchain revolution that is failing to happen. Without network effects, it never will. With an accidental combination of fearful incumbents and unambitious challengers conspiring against the openness that network effects require, it is time for the public sector to take the lead.

Tokenisation is not working. Or at least not in ways that will enable it to scale. Blockchains are an Internet technology, and the Internet is a network of networks. Which is why Internet success stories, from Amazon to Facebook to TikTok, have grown through network effects: the more people that use a service, the more valuable it becomes to the users.

What tokenisation needs to take off into self-sustaining growth is network effects. To be specific, the success of tokenisation depends on more and more issuers finding more and more investors. As that happens, network effects will take hold and shift the growth trajectory of tokenised assets on to a quadratic – and eventually, perhaps, an exponential - path into the future.

Securities and fund token markets are trivial in scale

But the starting point today is trivial. One recent estimate puts the global market capitalisation of both security and fund tokens at a mere US$33.8 billion in March 2024. (1) That modest figure amounts to 0.004 per cent of the value of all outstanding bonds (US$129.8 trillion at end-2022) and equities (US$101.2 trillion), (2) mutual (US$63.1 trillion) (3) and exchange-traded (US$80.6 trillion) funds and over-the-counter derivatives (US$618 trillion). (4)

To reach the US$5 trillion of tokenised securities and funds predicted for 2030 by Citi (5), the tokenisation markets will need to grow nearly 150-fold. To attain the US$16.1 trillion predicted for the same date by Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the markets will need to grow nearly 500-fold. (6) Reaching these goals implies compound annual growth rates of 130-180 per cent, which are unachievable without network effects.

These are demonstrably absent today. A review of the Future of Finance databases of significant “events” in securities and funds tokenisation finds that, although activity has increased steadily since 2016 (see Chart 1 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”), more than half of events recorded are not issues of tokens. Majorities are Proofs of Concept (PoCs) or Pilot Tests which do not go into production or largely cosmetic public relations exercises (see Chart 2 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”).

Much progress is more apparent than real

An official experiment, the European Union Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) Pilot Regime, introduced in March 2023 to encourage financial market infrastructures to test blockchain technology in the issuance, trading and settlement of tokenised securities, managed in its first year to attract just four applications (two trading platforms in Germany and a settlement system from each of the Czech Republic and the Netherlands) and a further eight inquiries. (7)

What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say

The Future of Finance databases cover securities and fund tokenisation “events.” In other words, they monitor not just token issues, but Proofs of Concept (PoCs) and Pilot Tests, platform launches, partnerships, acquisitions, legal and regulatory changes and other significant announcements. Collectively the events suggest that activity is growing (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

But a database covering seven years of events since 2017 still contains less than 10,000 data points, and in both the securities and the fund markets, majorities of the “events” are not records of tokens actually being issued or exchanged (see Chart 2). Alongside token transactions lies a great deal of posturing and a modicum of continued experimentation.

Chart 2

The databases also show that activity is concentrated among a relatively narrow group of financial institutions that are prepared to pioneer tokenisation. 260 separate firms are mentioned at least once in the databases but, for two out of three of them, a single instance is all they manage (see Chart 3). This is a counter-intuitive finding, not just because most institutions claim to favour a collaborative approach to tokenisation, but because tokenisation is built on blockchain - an open-source, composable digital technology whose success depends on network effects.

Chart 3

Even against the low bar of being mentioned at least five times, the databases find a mere 17 financial institutions are engaged in tokenisation at a more than superficial level. Just six banks (Goldman Sachs, Credit Agricole, HSBC, J.P. Morgan, Société Générale and UBS) are mentioned more than five times in the security token database. In funds tokenisation, no bank enjoys even that accolade. Among exchanges, just four – ADDX and SGX in Singapore and SDX and Luxembourg Stock Exchange in Europe – account for three out of four appearances in the data.

In funds (see Chart 4), where asset managers are widely assumed to be enthusiastic about issuing tokenised funds, just three managers account for a quarter of all activity and a dozen for half of it – and their interest demonstrably revolves around distribution (gathering more assets to manage) rather than investment (obtaining higher returns for their investors).

Sell-side pioneers interested in teasing out the requirements of the buy-side are in practice re-learning something they knew already: that asset managers see the potential of tokenisation but will not invest to bring it about and – still more predictably - expect to be able to invest in digital assets without making any changes to the systems and processes they use in traditional financial markets.

Chart 4

Nor are most asset managers acting directly to propel tokenisation forward. The majority are participating at the invitation of the sell-side, which is assuming the risk and cost of building platforms they hope the buy-side will one day use.

Banks and technology vendors account for two thirds of the institutions active in securities tokens and nearly half the institutions active in tokenised funds (see Chart 4). Even in funds tokenisation, where asset managers have most to gain as issuers, banks and technology vendors easily outweigh asset managers as drivers of change.

In developed equity markets, by contrast, there are already options to trade major stocks around-the-clock and the marginal cost of buying ten or 100 shares versus 1,000 is nugatory. So investing to tokenise equities looks as if it will yield a lower return than debt. Debt is also more useful than equity as collateral, but often hard to mobilise, especially across borders, where it is usually trapped in custodian banks and central securities depositories (CSDs). The level of interest in tokenising securities financing transactions (Chart 5) reflects this opportunity.

In fund tokenisation there is an equally clear bias towards alternatives and money market funds. Alternatives (real estate, private equity, hedge funds) not only lack standardised infrastructure but have minimum ticket sizes that restrict distribution. Tokenisation can in theory improve operational efficiency and (via fractionalisation) broaden distribution of alternative funds to investors with less money to invest.

Tokenised money market funds, on the other hand, can be sold to digital asset traders that need vehicles to park cash without re-entering the traditional banking sector (tokenised money market funds are, in effect, an alternative to Stablecoins). Tokenised money market funds can also be used by the same trading houses as collateral for credit. At current yields, they are easy to sell to end-investors too.

Chart 5

These preferences express the lack of ambition in a more profound sense too. For the most part, the assets that are being tokenised exist already. This is obvious in the case of real estate, commodities and fine art, all of which are ultimately physical. But it is equally true of hedge and private equity and mutual and indeed real estate funds, which continue to be available in analogue as well as tokenised or digital form.

Chart 6

Of the tokenised fund issues captured by the Future of Finance database, more than 95 per cent are what can be called “asset-backed” tokenisations: the funds continue to exist in their traditional form and tokens can be exchanged for the traditional alternative (see Chart 6). This is less true of the security token issues captured in the database, half of which are available in tokenised form only, but the implication is still clear: two out of three tokenisations recorded in the Future of Finance database are “asset-backed.”

Even progress that appears solid melts into air on closer inspection. There was considerable excitement, for example, about the high volume of structured notes being issued in digital form in Germany under the Gesetz zur Einführung von elektronischen Wertpapiere (eWpG) law on electronic securities (see the Sidebar “Securities Token Laws and Regulations in Seven Jurisdictions”). They turned out to be digital in terms of issuance only. The assets are otherwise settled and serviced in the same way, and by the same institutions, as traditional securities. (8)

Of course, none of these initiatives is useless. They have created a repository of practical knowledge of how to issue, buy and sell, settle and safekeep security, fund and cash tokens. Most experiments are collaborative. By facilitating the sharing of knowledge and ideas, collaboration accelerates progress, because firms can contribute what they do best and successes generated by one firm can be used by others.

But the value of continuing such exploratory activity is questionable. Indeed, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that many participants in these projects are using them not to make progress in tokenisation but to feign interest in it. Most members of a consortium contribute little or nothing and are interested mainly proving that they are “doing something” about tokenisation or at best in acquiring knowledge at low cost.

With more passengers than drivers, collaborations decay over time. Participants resent the fact that they are paying or contributing more than others. Projects get distorted by their growing appetite to tailor the outcome to meet their particular needs. A reluctance to share any useful “intellectual property” created sets in, undermining the rationale of working together. If perpetual collaboration is not designed to slow progress down, it might as well be.

Real progress depends on a handful of incumbent institutions

The superficiality of engagement with tokenisation at most institutions is starkly evident in the Future of Finance databases. These show that consistent involvement is confined to a group of just six banks and four exchanges. Two out of three firms that take part in a tokenisation “event” have yet to participate in another one (see Chart 3 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”).

Asset managers, which are vital as buyers of tokenised securities and issuers of tokenised funds, are scarcely engaged at all in the tokenisation of securities (see Chart 4 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”). They are involved of necessity in the issuance of tokenised funds but are (with few exceptions) adamant that it is up to the sell-side to make token issuance and investment as painless for them as possible.

Worse, in tokenising funds, asset managers have become by default the principal proponents of the least disruptive form of tokenisation: the “asset-backed” variety, in which the token is a mere digital representation of the original asset. Investors in “asset-backed” tokens own no more than title to the underlying asset, which must continue to exist, whether it is a physical asset such as a building or an abstract asset such as a security or a fund.

Almost all the tokenised funds captured by the Future of Finance databases are asset-backed (see Chart 6 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”). The tokenised variant can be no more than an additional class of share in the original fund, as if tokenisation is a matter comparable to choosing the currency or schedule of fees. But even in the case of the security tokens captured by the databases, half are asset-backed.

Most tokenisations are superficial

This matters, because an “asset-backed” token is not an asset in its own right. An “asset-backed” token is comparable to the “depositary receipts” offered by custodian banks to investors wanting to hold foreign securities in custody in their own currency, or the “wrapped” equities offered to investors by cryptocurrency exchanges, or the “tokenised deposits” issued by banks against their balance sheet liabilities as a form of digital money.

A genuine token, on the other hand, exists in digital form only. Its value depends not on anything external but solely on the stream of income it pays (also in tokens) and its value when exchanged between sellers and buyers. It is a true digital asset, not a representation of a conventional asset, or title to another asset. It is closer in conception to the “native” coins issued to fund blockchain networks such as Bitcoin (Bitcoin), Ethereum (Ether) or Solana (Solana).

In software terms, true tokens are “executable objects” that cannot exist outside computers. In English law, such tokens fit neither of the existing legal categories of property, where possession must be either physical (such as a gold coin) or enforceable by law (such as a security). Indeed, the United Kingdom Law Commission, a statutory body that recommends reforms of the laws of England and Wales, has had to invent a new form of property to accommodate tokens as true digital assets. They are, according to the Commission, “data objects.” (9) In other words, they are strings of data that are inseparable from the digital systems in which they reside.

Blockchains are not databases and tokens are not entries in databases

The digital systems on which tokens reside are blockchains. Though they are often described as databases, blockchains are not databases. They are actually computers - or at least virtual computers (the Ethereum Virtual Machine is not mis-named) that rely on networks of physical computers. It is because they are computers that blockchains charge “gas fees” for use of computing time and why they face criticism for excessive electricity consumption.

One implication of this is that, contrary to popular perceptions, true tokens are not entries in a database but “executable objects” in a computer. The transactions which change the status of who owns what are less like changing entries in a ledger than the standard computational process of changing from one “state” to another in response to inputs in order to arrive at one of a finite number of “states”: the true “state” of the data. (10)

These returns to the true “state” are why blockchains can be described as “immutable ledgers.” Effectively, tokens sit on digital ledgers. All transfers of value are executed by flows of tokens between addresses on digital ledgers. Those flows can be initiated automatically by “smart contracts” embedded in the tokens.

“Smart contracts” can self-execute a payment, for example, when a third-party data source (an “oracle”) indicates an event has occurred (such as a record date for a dividend payment) or conditions are satisfied (such as a decline in the price of collateral triggering a margin call).

Tokens can also interact with third-party “smart contracts” stored on blockchains, enabling services supplied by third parties – the decentralised applications, or DApps, that enable users of Decentralised Finance (DeFi) protocols to borrow, lend, trade, invest and pay with cryptocurrency tokens are an example – to be executed automatically.

In effect, tokens held on blockchains and tokens transferred between addresses on blockchains transform both the ownership and the transaction processes in asset markets. Purchases and sales, and the subsequent updating of records of ownership, are subsumed into a single process.

The transactions, and the registered owners, can then be shared with all parties to a transaction simultaneously.

Because tokens are simply strings of data (or code) they can express anything. Cash, debt, equity, derivatives, funds, indeed any financial asset that can be conceived, can be created and combined as flows not of cash but of tokens.

Tokens can express any financial asset or liability in standard components

In this sense tokens are “composable” in the same way that Open-Source code is “composable”: the code has to be written once only and can then be re-used and combined to create new products. This “composability” is what accounts for the speed of innovation in the cryptocurrency markets.

The openness and “composability” of code also makes possible the “single programmable platform” or “unified ledger.” This idea was first articulated for digital payments by a private sector group - the Regulated Liability Network, or RLN (11) - in November 2022 before being seconded by the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) in the same month as the “X-C platform” (12) and by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in a paper of June 2023. (13)

A unified ledger would be not a single ledger but a network of multiple ledgers specialising in different asset classes (including cash) but which operate to the same technical standards, making them inter-operable.

On such a network of networks, tokens and flows of tokens equivalent to the traditional forms of cash, securities and funds could be issued, settled “atomically” - the simultaneous exchange of digital assets for digital money, with the transfer of one contingent upon the transfer of the other - and safekept and serviced in the same way.

In sum, true tokens issued on to interoperable blockchain ledgers would be “composable” into combinations of assets (for investors) and their countervailing liabilities (for issuers) that can be tailored to specific needs and objectives. In theory, portfolios could be constructed that meet the individual needs of retail investors. Likewise, issuers could structure equity capital raisings or debt financings that match exactly their outgoings.

The astonishing inefficiency of the status quo

In a universe without the legacy of the past, a system of this kind – one in which capital value took the form of combinations of tokens, and transfers of value took the form of movements of tokens, each made up of standardised components described in code - would swiftly devour the whole of the traditional money and capital markets. Why? Because the present system is astonishingly inefficient by comparison.

In the traditional financial markets every class of asset – equity, debt, funds, derivatives and alternatives – inhabits its own universe, with its own issuance, trading, settlement, custody and servicing processes. Each asset class also supports a string of specialists that lie between issuers and investors.

These intermediaries are paid for issuance (investment banks), listing (stock exchanges), safeguarding the integrity of the issue (central securities depositories, or CSDs), managing portfolios (asset managers), trading assets on behalf of asset managers (brokers), netting purchases and sales (Central Counterparty Clearing houses, or CCPs), and settling transactions and safekeeping assets (custodian banks).

Unlike blockchain-based systems such as the “single programmable platform” or “unified ledger,” in which all parties to all transactions in all assets see the same information about a transaction or an asset simultaneously, the high levels of intermediation in traditional markets require repeated flows of data between the various intermediaries to reconcile, maintain and update records of transactions and ownership.

Once an order to execute a securities trade across borders is made, for example, notices (of execution), matches (of trades), confirmations (of trade details) and instructions (to settle)

are processed through exchanges, global and local brokers, asset managers, CCPs, specialist matching services (such as DTCC CTM (14)), global custodian and sub-custodian banks and CSDs. Notifications (of corporate actions) and collections (of entitlements) generate further flows of data between intermediaries.

Similarly, placing an order to buy or sell shares in a fund initiates a series of exchanges of

data between intermediaries that populate the space between the investor and the asset manager. Wealth managers and fund platforms use order-routing systems to send subscription, redemption and switching orders to transfer agents, which settle transactions by matching cash subscriptions with shares issued, and then update a register of who owns what.

Further flows of data ensue, to the fund accountant that values the fund every day, the depositary bank that checks the fund complies with the terms of its prospectus and its regulatory responsibilities, the auditor that certifies the financial statements of the fund, and the authorised corporate directors that are responsible for the day-to-day management of the fund.

Unlike tokens issued on to blockchain networks, where all parties are privy to the same data about assets and transactions, the data every intermediary holds in their proprietary computer systems have to be reconciled with the data held by every other intermediary in their proprietary computer systems. Unlike a blockchain network, every party is working on a different computer system and none has a complete view of the status of a transaction or asset (the true “state” of the data).

In traditional post-trade processing errors and omissions abound

The sheer number of parties to a transaction, each of them operating their own systems, is prone to errors and omissions which add to operational costs. If the details of a bond issue, for example, have to be keyed into a dozen different systems, mistakes are bound to occur. To minimise these, structured data formats such as FIX and SWIFT and FpML are used, but not every intermediary uses them or uses the same version.

Even when data is exchanged in standard formats, mistakes are common. Further back-and-forth is required to “reconcile” the differences, so the agents to the buyer and the agents to the seller can agree what has happened. Inevitably, some transactions fail altogether because unmatched, inadequate, out-of-date or erroneous data means securities to deliver cannot be found, trade details do not match and the Standing Settlement Instructions (SSIs) that list the names of the relevant custodians and payments banks and account names and numbers are wrong. (15)

Even in a relatively efficient market such as the euro-area, 6½ per cent of trades (by both volume and value) are failing to settle on time, generating financial penalty costs of €1.7 billion and credit charges of an estimated €1.425 billion plus additional collateral maintenance and sourcing costs. (16)

HQLA-x – operators of a blockchain-based collateral management platform - estimate that collateral management inefficiencies, such as maintaining large buffers of cash and securities in multiple markets around the world to ensure transactions settle on time, currently cost (loosely defined) Tier 1 banks €50-100 million a year each. (17)

The conservatism of incumbents is explicable

The blockchain alternative has obvious advantages over these expensive and disorderly processes. The parties to a transaction would not need to compare their records with each other. In fact, they would not need to maintain their own records of ownership and transactions at all, or the systems to host them. So why does such an inefficient system persist?

Because it is only a short step from jettisoning records and systems to jettisoning intermediaries. After all, if self-executing “smart contracts” can replace any function with code, and transactions settle atomically, there is no need for CSDs and brokers and CCPs and custodian banks to match and net and settle trades, repair failing transactions, and distribute entitlements.

True digital asset tokens have no need of the intermediaries required to maintain, reconcile and update records of transactions and ownership. In this crucial respect, they differ sharply from “asset-backed” tokens.

This does not mean “asset-backed” tokens will disappear. They cannot, because any asset that is not purely financial in nature – a class that includes real estate, commodities, fine art and other physical objects - must retain ties to the real world. Which means asset-backed tokens will always require reconciliation between the tokens and the underlying assets, which in some cases exist only in old-fashioned accounts and book-entry registers, which must be preserved also.

The mistake is to universalise a model adapted to the physical world to contractual abstractions such as equity, debt, derivatives and funds. There, the attraction of retaining real-world practices and institutions is that it does not necessitate any alteration to the eco-system of intermediaries that extract value at various points between the issuer and the investor.

It is easy to understand the attractions of leaving the status quo undisturbed. Tension between incumbents (which have much to lose) and innovators (which have much to gain) is unavoidable, and the temptation for innovators to suppress it by “working with” incumbents is strong.

Which is why the Future of Finance databases record incumbent stock exchanges, commercial and investment banks, custodian banks, central securities depositories (CSDs) and asset managers working with technology vendors and start-ups specialising in tokenisation (see Chart 4 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”).

In fact, one reason why “asset-backed” tokens have become the default method of tokenisation (especially in funds) is that “asset-backed” tokens preserve intermediaries. Asset-backing means incumbent service providers can support change without putting existing revenues at risk. To further protect those revenues, incumbents are building their own tokenisation engines, to reduce the risk of losing clients to more adventurous competitors.

As the Future of Finance databases record, a number of investment banks (such as Goldman Sachs) and custodian banks (such as HSBC) have built tokenisation platforms. Stock exchanges (such as SIX), fund platforms (such as AllFunds) and fund order-routing networks (such as Calastone) have built blockchain-based services for similar reasons. But these are hedges, not bets. Their proponents do not expect the status quo to evaporate.

Tokenisation is being diverted into areas where disintermediation is not a threat

But the principal means by which existing revenues are being protected is by diverting capital and entrepreneurial energy into areas where major revenue streams are not at risk, and new revenue streams may even open up. Custodian banks are already custodying cryptocurrencies. Banks, CSDs, exchanges and (in the hope of placating incumbents) blockchain technology vendors are focused on real estate and privately managed assets as early candidates for tokenisation.

For now, the Future of Finance databases indicate the low-risk options lie in the primary market for bonds, the relatively novel green bond markets (where lack of data has led to allegations of “greenwashing” that tokenised issues can address) and a string of alternative asset classes such as private equity, hedge and real estate funds, but also loan receivables, gold and diamonds (see Chart 5 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”).

In funds, the principal benefit of tokenisation is the opportunity to broaden the distribution of alternative strategies by lowering minimum subscription amounts. The databases record reductions from as much as US$5 million to US$10-20,000, and even to as little as US$1,000. This appeals to asset management clients, as does the prospect of convenient access to precious metals and minerals – a logic that is extensible to all manner of physical stores of value, such as fine art, fine wine, expensive watches and classic cars.

By focusing on asset classes inaccessible to retail investors (such as private equity and hedge funds) or less intermediated investments (such as gold and diamonds) or asset classes with demonstrable operational shortcomings (such as the primary market process for European bonds) tokenisation pioneers are not putting established revenues at risk (see Chart 5 in the Sidebar “What the Future of Finance Tokenisation Databases Say”).

The harsh prospect of the displacement or even the extinction of incumbents can be pushed into a future that lies beyond a current “period of coexistence” of indeterminate length between the old way of doing things and the new. The idea of “backwards compatibility” is even touted as a virtue. It also provides useful cover for a policy of wait-and-see, letting the handful of eager pioneers bear the costs and take the risks.

If all else fails, there is regulation. The incumbents are regulated entities, and so are their clients, and it is plausible to argue that tokenisation lies outside current regulatory perimeters. But this is increasingly untrue. In a series of important jurisdictions – Germany, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Singapore, and the United Kingdom – law as well as regulation is far from hostile to token experiments (see Sidebar, “Securities Token Laws and Regulations in Seven Jurisdictions”). In pleading for regulatory clarity incumbents are pleading their own case, because they know they can afford the costs of compliance and start-ups cannot.

The incumbents are regulated entities, and so are their clients, and it is plausible to argue that tokenisation lies outside current regulatory perimeters. But this is increasingly untrue.

Securities Token Laws and Regulations in Seven Jurisdictions

European Union

In the European Union, securities tokens are regulated as securities, chiefly under the second (2018) iteration of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) and the Central Securities Depositories Regulation (CSDR) but also the Prospectus Directive (2017), the Short Selling Directive (2012), the Market Abuse Directive (2014), the Transparency Directive (2004) and the Settlement Finality Directive

(1998). Indeed, the flagship Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation, which came partially into force on 29 June 2023 and will be fully in force by December 2024, explicitly excludes securities (as opposed to cryptocurrencies, Stablecoins and e-money). Instead, the EU is initially tackling mismatches between security tokens and current securities law and regulations via the so-called Pilot Regime, which came into force on 23 March 2023. The Pilot Regime allows market infrastructures such as established trading platforms, central counterparty clearing houses (CCPs) and central securities depositories (CSDs) and new market entrants to obtain temporary, six-year exemptions from current regulations to conduct experiments in the issuance, trading, settlement and custody of both native and non-native security and fund tokens on blockchain networks to inform future measures to bring token regulation into line with current securities regulation. (18) Market infrastructures participating must keep the capitalisation of equity issues below €500 million; bonds below €1 billion; and mutual fund assets under management below €500 million. (19) When the aggregate value of tokens traded reaches €9 billion, the market infrastructure must “transition” out of the Pilot Regime. So far, the Pilot Regime has attracted just four applications and none has yet launched a service. (20) Initial queries from potential service providers focused largely on clarifying instruments eligible for tokenisation and the regulatory reporting and record-keeping requirements. (21)

Germany

On tokenisation, Germany has acquired a reputation as the most progressive jurisdiction in Europe. The government codified the requirements necessary to obtain a digital asset custody (Kryptoverwahrgeschäft) licence – essentially, capital of €125,000 plus demonstrable competence to safekeep digital assets - from the regulator, the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) under the German Banking Act (KWG) in January 2020 (though the licence is not “passportable” and so cannot be used elsewhere in the European Union (EU)). In 2021 the German government enacted an Electronic Securities Act (Gesetz über elektronische Wertpapiere, or eWpG) which allows issuers to issue bearer bonds without a physical certificate on to electronic registers at a central securities depository (CSD) or other service provider. Though confined to bonds, the eWpG secured property rights in security tokens for investors under German law for the first time by dispensing with the previous need for physical certification. The eWpG also introduced the concept of a digital asset ownership registration function (Kryptowertpapierregisterführung) under the German Banking Act (Kreditwesengesetz– KWG). Any firm providing such registration services must obtain a licence from BaFin, which is contingent on showing capital of €730,000 – a sum which, being nearly six times that required of a digital asset custodian, testifies to the importance of the security and integrity of the digital registration function to the development of a security token market in the German context. (22) Importantly, the eWpG also amended the German Capital Investment Code (Kapitalanlagegesetzbuch – KAGB) to enable the issuance of units in funds in electronic rather than certificated form. In June 2022 the German government introduced a Regulation on Crypto Fund Units (Verordnung über Kryptofondsanteile – KryptoFAV) that permits the issuance of fund units or shares on to blockchain-based registers. The depositary to the fund, or a third party instructed by the depositary to the fund, can act as the registrar.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg is unusual in having implemented clear regulations for using blockchains to issue native tokenised securities. By laws of 1 March 2019, 22 January 2021 and 17 March 2023 (often referred to as “Blockchain laws 1, 2 and 3”) Luxembourg has encoded in law three key functions of a tokenisation market. First, the registration of ownership of security tokens in digital form only is permissible. Secondly, the issuance of security tokens on to blockchain networks is permissible. Thirdly, security tokens can be used as collateral for borrowings, which increases the attractions of holding them. A number of digital asset businesses have chosen to establish entities in Luxembourg to take advantage of this regulatory clarity.

Switzerland

The Swiss Law on Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT Law) that came into effect in August 2021 encompassed changes to ten existing laws to enable security tokens to be issued, traded and safekept on traditional as well as blockchain-based platforms. Crucially, the DLT Law introduced the concept of the transferable, ledger-based security token that can exist in digital form only, replacing a cumbersome process by which uncertificated securities (into which category securities tokens issued on to blockchains fall) could be transferred only by written assignment even if they were already recorded on an electronic register. Swiss law is less clear than some other jurisdictions on which types of tokens count as security tokens – the crucial distinction is that the token grants the holder rights against an issuer - but in practice the Swiss regulator, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), tends to treat any token issued and tradeable on a blockchain network, and linked either to a real-world asset or (akin to the Howey Test) to the future success of a business venture, as a security token.

Singapore

As the regulator, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has not initiated new laws applicable to security and fund tokens. It has instead made clear that the licensing and prospectus requirements of the existing securities law – the Securities and Futures Act (SFA) of 2001 - apply to security and fund tokens. What determines whether a digital asset is a security token is whether it represents a liability of a corporate issuer (shares or bonds) or a right or interest in a fund. Fund tokens are subject to further regulation under the existing Securities and Futures Offers of Investments (Collective Investment Schemes) Regulations of 2005 and the Code on Collective Investment Schemes. Tokens backed by assets such as precious metals are regulated separately under the Commodity Trading Act (CTA) of 1992. The MAS also embarked in May 2022 on an active regulatory Sandbox initiative (“Project Guardian”) in which it collaborates with market participants to run pilot schemes to explore how digital assets can be issued, traded, settled and safekept on blockchain networks while managing the risks to financial stability and integrity. One pilot proved that tokenised deposits and tokenised government bonds could be exchanged and settled on a public blockchain. A pilot to issue, distribute and service wealth management products such as structured notes and actively managed certificates in tokenised form on to blockchains was launched in November 2022.

There is no single model for bringing securities laws into line with tokenisation. Some jurisdictions apply existing laws, some adapt existing laws, and others write new laws.

United Kingdom

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) made clear in a policy statement of July 2019 that securities tokens that share the characteristics of securities - such as ownership rights, transferability, repayment of a specific sum of money or entitlement to a share in future profits - are regulated as securities under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) (Regulated Activities) Order 2001. (23) This means issuers, and firms active in the security token markets, must obtain a licence from the FCA and follow the rules – still set by the 2017 Prospectus Directive and the 2018 Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) of the European Union (EU), though these are now under review following the United Kingdom withdrawal from the EU - that govern the securities markets. A market consultation of July 2022 by Her Majesty’s Treasury found token market participants were still seeking further legal and regulatory clarity over several issues, including lex situs (which jurisdiction’s laws apply when tokens are held on systems scattered across multiple countries); novel features such as “smart contracts”; the poor fit between the Uncertificated Securities Regulations (which enable securities to be evidenced and transferred electronically) and tokens in terms of settlement finality; the irrelevance to tokens of terms such as “account” and “book-entry” used in current legislation; and especially the requirement under the Central Securities Depositories Regulation (CSDR) of the EU, most of which still applies in the United Kingdom, that trading venues must use a central securities depository (CSD) to settle and record transactions. But the main immediate consequence of the Treasury consultation was the inclusion in the Financial Markets and Services Act, which became law in June 2023, of language establishing a Financial Market Infrastructure (FMI) Sandbox, akin to the Pilot Regime of the EU (24). In the Sandbox, firms can test the ability of tokens issued on to blockchains to create a cheaper, less risky, better integrated and more transparent securities market infrastructure without breaching current regulatory obligations or fragmenting the post-trade market or placing excessive demands on firms to source liquidity to settle transactions “atomically.” (25) The Digital Sandbox opened on 1 August 2023. Separately, in its February 2023 paper on the future of the asset management industry in the United Kingdom, the FCA invited market participants to propose changes to regulations to encourage tokenisation of mutual fund shares or units, as opposed to tokenisation of underlying assets of a fund. The paper speculated that tokenisation could facilitate the individualisation of investment portfolios, reduce costs through disintermediation of functions such as registration, and improve liquidity in certain asset classes, notably infrastructure and real estate. In tandem with the Technology Working Group, which reports to the Treasury’s Asset Management Taskforce, this led to the publication by the Investment Association of a less-than-radical multi-stage “blueprint” for the tokenisation of funds in the United Kingdom. (26) The Digitisation Taskforce set up by the government in July 2022 to explore how to improve capital-raising by enhancing relationships between issuers and investors and reducing the cost of owning, trading and settling securities, published an interim report in July 2023. (27) It recommended an end to paper share certificates; easier ways to exercise shareholder rights, including votes; and discontinuation of payment by cheque.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the United Kingdom has drawn a clear regulatory distinction between cryptocurrencies and security tokens.

United States

The federal government of the United States has not developed token-specific laws. This is because the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) believes and has argued consistently since the Initial Coin Offering (ICO) boom of 2017-18 that a wide variety of tokens are securities that need to be regulated under existing federal securities laws. Under those laws, an issuer may not sell securities unless the offering is either registered with the SEC or declared exempt by the SEC. Registration requires the issuer to disclose detailed information about the company, the offering, and the securities, including audited financial statements. Federal law also obliges all intermediaries engaged in the securities industry to register with the SEC or a self-regulatory organization such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). The aim of regulating intermediaries is to protect investors through measures such as obliging firms to keep customer assets separately from proprietary assets with an independent custodian and ensuring investors have access to insurance against loss via the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The principal determinant

of whether a token is a security is the Howey Test, which assesses whether a token is a security by whether there is (a) an investment of money (b) a common enterprise in which the purchaser’s and the promoter’s interests are aligned (c) an expectation of profit on the part of the purchaser and that those profits derive from efforts of others (e.g., the issuer of the token). A second assessment, the Reves Test, assumes a token is a security unless a similar instrument has been judicially determined to fall outside the definition of a security (the exceptions are determined by the courts on the basis of the motivations of the seller and the purchaser, the distribution of the instrument, the expectations of the investing public and any alternative regulatory status for the token). The broad application by the SEC of the Howey Test in particular to a wide range of tokens, including many cryptocurrencies most jurisdictions do not classify as securities, has proved contentious.

The logic of the Internet dictates disintermediation

But in the end, incumbents are fighting a rearguard action. What makes an innovation disruptive is precisely the fact that it disrupts the incumbents. And true tokenisation will do exactly that. Incumbents can slow its progress down but in the end tokenisation will replace existing forms of securities and funds; existing computer systems; and existing intermediaries.

That implies an uncomfortable future for specialists in portfolio management (wealth and asset managers), research and execution (brokers), listing and trading (exchanges), liquidity provision (market makers), cash payments (payments banks), netting and risk management (CCPs), issuance, trade matching and settlement (CSDs), safekeeping and asset servicing (custodian banks), registration and settlement (transfer agents), valuation (fund accountants), data (data vendors) and compliance (depositary banks and management companies).

But they have to be discomfited because it is only by eliminating these functions that blockchain can deliver a return on investment. After all, each of the intermediaries in the traditional system exacts a toll – paid ultimately, it should not be forgotten, by issuers and investors, meeting whose needs is the point and purpose of the entire system of securities and funds - in the shape of a fee or bid/offer spread or ad valorem charge.

That such an extended order of intermediation is expensive seems obvious. Whether it is inefficient as well can be debated. Institutional investors have shown a strong appetite for the continued use of intermediaries, but then they are rarely spending their own money, and resent it when they are obliged to do so (despite regulatory pressure, asset managers in particular have retained a strong penchant for charging third party costs to the fund).

There is also a literature that argues against the view that the “middleman” adds nothing but cost in financial and other markets. The more conservative voices in tokenisation are apt to allude to it when arguing against those who believe that nothing but technology needs to stand between issuers and investors.

This is not to accuse incumbents of bad faith. They are condemned to think and say what they do by the framework within which they operate. They may even believe that they add value and will in some cases be right. But in the end, even the strongest convictions must yield to the formidable logic of the Internet, which is that the key to scale is network effects, and that the key to network effects is openness.

A strategy that leavens cunctation plus limited but ostentatious investments in PoCs and Pilot Tests and partnerships will not yield network effects. Incrementalism is the default mode of the modern corporation because it increases sales without excessive investment - think Apple iPhone – and it works for a time because user needs develop more slowly than the capabilities of digital technology.

But it is precisely this fact – that bit-by-bit improvement does not keep up with technological improvements - that gives outsiders a chance to overtake incumbents. The experience of tokenisation so far will have reassured the leadership of banks and stock exchanges and CSDs that they can control the pace of change. But the history of technology suggests that current improvements to blockchain technology – including their speed and scalability – will create opportunities for new entrants to innovate in ways that compound quickly, introducing disruptive network effects.

Incumbents are trying to build closed networks

Incumbents are of course working hard to keep new entrants out, by hoarding their client bases, using experiments and partnerships to plunder the knowledge of entrepreneurs and innovators, insisting on closed rather than open private or public “permissioned” blockchain networks and calling for greater regulatory scrutiny that smaller firms cannot afford. Unfortunately – and this may reflect the pervasive influence of the venture capital industry in funding start-ups – this is forcing many new entrants to think the same way.

The lack of inter-operability between blockchain protocols is not an accident. It reflects the determination of the founders of blockchains to make it hard for customers, assets and activity to defect to another protocol. Their model, contrary to cypherpunk mythology and Web 3.0 propaganda, is to replicate Big Tech successes like Facebook and gaming giants such as Roblox, that aim to capture and control their users (and purchase any competitors that appear threatening).

What tokenisation needs is the opposite of this. It needs open networks, not closed ones. In this case, openness means enabling anyone to establish a blockchain network that can grow without running into barriers erected by incumbents.

If the companies that are going to build the token markets cannot be confident that they will retain the long-term rewards of their effort and investment, they will not secure funding from venture capitalists and can at best aim only to sell their inventions and innovations to the incumbents. A pattern of consolidation has emerged already in digital asset custody. (28)

The case for a public blockchain infrastructure

Which prompts a disarming thought. Blockchain is an Internet technology, and the invention and early successes of the Internet depended not on private money and ingenuity but on public science and public investment.

The Internet itself was pioneered by the Defence Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) and the then State-owned British Post Office - both AT&T and IBM refused invitations to help, seeing it as threat to their existing business - as a decentralised communications network in the event of nuclear attack.

DARPA also funded the TCP/IP protocol that specifies how data is exchanged over the Internet. Likewise, the SMTP protocol, the network standard for sending emails, was invented by publicly funded engineer Jon Postel to enable the first user of the TCP/IP protocol – the publicly funded Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) - to send and receive emails.

A governing body could issue tokens to investors of sufficient value to fund the construction and maintenance of a public blockchain infrastructure.

It was another publicly funded scientist, Tim Berners-Lee, then working at CERN, who in 1989 invented the HTTP protocol that enables the Web (the essence of the Internet for most people, because it links pages through the Internet).

All the subsequent innovations that drive the Internet – notably the privately owned browsers and emails everybody uses, but also social media and e-commerce – depend on these three free-to-use protocols. (29) In effect, TCP/IP, SMTP and HTTP turned the Internet into a general-purpose technology comparable to electricity that enabled entrepreneurs and innovators to create Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, Instagram, PayPal, YouTube, TikTok and Twitter (now X).

If tokenisation is now stymied by the imbalance of money and power between the incumbents and the innovators - which it certainly appears to be – the early history of the Internet suggests a solution. This is to build a public blockchain infrastructure open to entrepreneurs, innovators and academics to create and build anything they like (within the law).

The idea is not as outlandish as it sounds. LACChain in the Americas (led by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)) is a public-private initiative to build and manage inter-operable public permissioned blockchain networks open to any participant prepared to abide by the rules of the network to pursue any purpose that is not criminal.

LACChain and a similar exercise in Spain (30), do not exclude big businesses, but are based on a recognition that a neutral blockchain infrastructure that is cheap, reliable, compliant and inter-operable can encourage entrepreneurial activity in a way that private blockchain networks cannot. Such a model certainly has the potential to stimulate innovation and competition in the development of new products and services, including tokenisation.

How to fund a public blockchain infrastructure

The question is how to establish a public blockchain infrastructure without relying on the incumbents for funding. The answer lies in the history and nature of the blockchain itself, and especially in the lessons of the Initial Coin Offering (ICO) boom of 2017-18. Ethereum, which is a general-purpose programming platform comparable to a public blockchain infrastructure, emerged from the early stages of the boom.

The boom itself proved that significant amounts of money could be raised by a process little different from crowd-funding. Although most of the money raised was lost or stolen - including US$50 million from Ethereum, prompting the “hard fork” that created Ethereum Classic - ICOs did raise US$31 billion between 2016 and 2018. (31)

That sum confirms that a governing body, organised like Ethereum as a Decentralised Autonomous Organisation (DAO), could issue tokens to investors of sufficient value to fund the construction and maintenance of a public blockchain infrastructure. If the investors included issuers, network effects would soon develop, because they would benefit from their own activity, in addition to developers scripting applications. Unlike most ICOs, the issue would fund a start-up with a revenue plan.

Tokens issued by DAOs obliterate the distinction in traditional capitalism between customers, employees, managers, shareholders and suppliers. In traditional capitalism the shareholders and the employees and managers benefit from success; in token capitalism, everybody does, including the customers, which would include both issuers and investors. That is what will drive network effects.

How incumbents might react to a public blockchain infrastructure

An interesting question is how the incumbents would react to the development of a public blockchain infrastructure. A token-funded alternative would exclude them from participation because it is axiomatic inside regulated financial institutions that investing in an issue by a DAO is impossible. This is less because of qualms about the quality and provenance of the tokens as an asset than the need to share the rewards with interests other than shareholders.

Their lack of engagement would be off-putting to potential users of a public blockchain infrastructure, especially in the absence of government or regulatory involvement. So it follows that (as with LACChain) official bodies will be needed to lend respectability and public assurance to the service. There is no reason why that should not include central banks. Making a central bank digital currency (CBDC) available on the infrastructure would reinforce network effects.

With that support, a public blockchain infrastructure would provide a viable and attractive alternative to proprietary blockchain networks. As it grew into a competitor to the traditional money and capital markets, incumbents would be forced to stop equivocating about tokenisation. As it happens, there are good reasons for them to abandon their equivocation anyway.

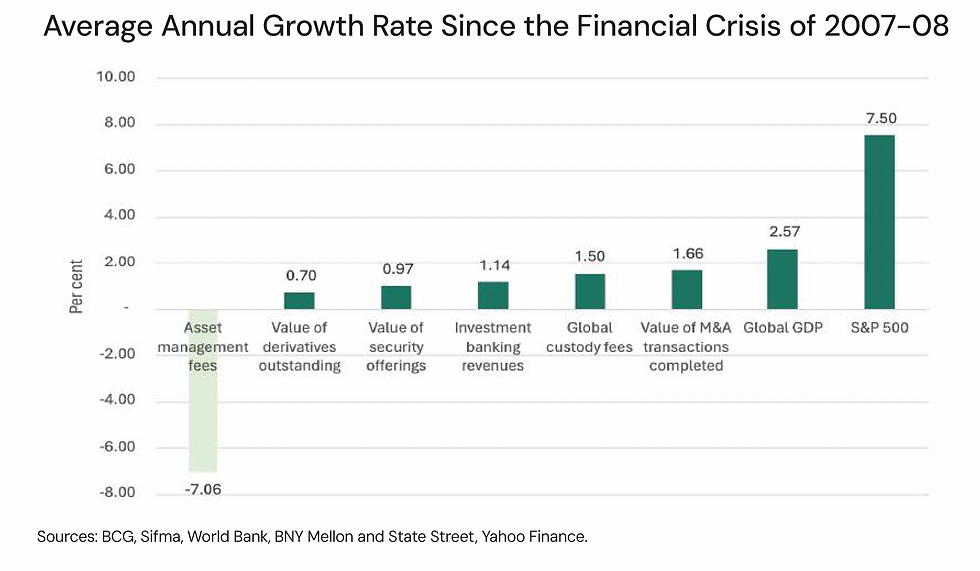

As Chart 1 shows, the asset management industry is in a quandary. Globally, assets under management (AuM) are stalling. Net new capital inflows are down, and most new money is also going into less profitable passive strategies. Clients are exerting strong downward pressure on fees. Yet costs are rising sharply. Consultants BCG predict that asset management profits are on course to halve unless drastic action is taken. (32)

The investment banking industry is in a less dire condition but, as Chart 1 also shows, revenues have risen far more slowly than stock markets and economies since the great financial crisis of 2007-08. The non-trading markets in which they make money, such as mergers and acquisitions and securities offerings, have also grown slowly. Re-regulation, and especially increased capital requirements, have made it much harder to make money in investment banking. In their trading franchises, investment banks are under sustained assault from independent trading platforms and market-makers which do not bear the same capital costs.

Global custodian banks also emerged from the financial crisis with an increased burden of regulatory obligations to protect investors and cut financial crime. The aftermath of the crisis added heavier operational capital requirements which are disconcerting for an historically off-balance sheet business. Regulators (especially in the United States) are now threatening to raise still further the costs of providing custody. (33) At the same time, the shortening of settlement timetables requires investment and promises to increase the costs of settlement failures. (34)

Chart 1

Incumbents can slow progress down but not halt it

In these circumstances, the limited interest in transformational technologies shown by asset managers, investment banks and global custodian banks, to say nothing of stock exchanges, CSDs and CCPs, in the Future of Finance databases is remarkable.

But then, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, the process of replacing the obsolescent or obsolete technologies and processes by newer and better ways of doing things is far more complicated than popular renditions of his theory of Creative Destruction imply.

Investment is costly and returns uncertain. Every new technology must be made to fit into existing processes, so no investment can be made in isolation from the rest of the business. Besides, changing technologies all the time would create a perpetual instability incompatible with running the existing business.

Last but far from least, the management of incumbents believe they have a duty to shareholders – which these days invariably includes themselves – to preserve the value of existing capital. As Schumpeter says, incumbents are condemned to “sabotage” cost-reducing improvements. Indeed, they “can and will fight progress itself.” (35) But progress tends to win in the end.

Replacing obsolete or obsolescent technologies is expensive and destabilising and the rewards for shareholders uncertain and distant. The incentives for management to do nothing are powerful.

(1) STOmarket.com

(2) Sifma, 2023 Capital Markets Fact Book, pages 11 and 13.

(3) Investment Company Institute, Worldwide Public Tables, 2023: Q4, Table 1.

(4) Sifma, 2023 Capital Markets Fact Book, page 15.

(5) Citi, Money, Tokens, and Games: Blockchain’s Next Billion Users and Trillions in Value, March 2023, page 9.

(6) BCG and ADDX, Relevance of on-chain asset tokenisation in `crypto winter,’ September 2022, page 7.

(7) Letter from Verena Ross, executive director of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) to the European Council, Commission and Parliament, 3 April 2024.

(8) See Future of Finance, Digital Asset Custody Guide, Issue 2, Regulation Matters, pages 40-41.

(9) Law Commission, Digital Assets: Consultation paper, 28 July 2022, paragraph 5.18, pages 80-81 and paragraph 10.33, page 164.

(10) Users of blockchains are incentivised to do the computational work needed to arrive at the “true state” by the rewards paid in Proof of Work and Proof of Stake schemes.

(11) The Regulated Liability Network, Digital Sovereign Currency, White Paper 15 November 2022.

(12) International Monetary Fund, A Multi-Currency Exchange and Contracting Platform, prepared by Tobias Adrian, Federico Grinberg, Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli, Robert M. Townsend, and Nicolas Zhan, Working Paper WP/22/217, November 2022.

(13) BIS Annual Economic Report, 20 June 2023, Chapter III, Blueprint for the future monetary system: improving the old, enabling the new, pages 85-118. See also the speech by Agustín Carstens, General Manager of the BIS, The future monetary system: from vision to reality, at the CBDC & Future Monetary System Seminar, Seoul, Korea, on 23 November 2023.

(14) The Central Trade Matching (CTM) utility owned and operated by the American CSD, the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), matches and confirms domestic and cross-border equity, fixed income and repo transactions.

(15) See separate article, “Reference data is the unlikely rocket fuel propelling us into a tokenised future” on pages 61 to 85.

(16) See https://futureoffinance.biz/european-capital-markets-are-inefficient-so-why-arent-european-csds-doing-more-about-it/

(18) Regulation (EU) 2022/858 of the European Parliament and of The Council of 30 May 2022 on a pilot regime for market infrastructures based on distributed ledger technology and amending Regulations (EU) No 600/2014 and (EU) No 909/2014 and Directive 2014/65/EU.

(19) European Securities and Markets Authority, Report on the DLT Pilot Regime: On the Call for Evidence on the DLT Pilot Regime and compensatory measures on supervisory data, 27 September 2022, page 11.

(20) See page 17 and footnote 7 above.

(21) European Securities and Markets Authority, Questions and Answers: On the implementation of Regulation (EU) 2022/858 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on a pilot regime for market infrastructures based on distributed ledger technology, 2 June 2023.

(22) See page 21 and Future of Finance, Digital Asset Custody Guide, Issue 2, Regulation Matters, pages 40-41.

(23) Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), Guidance on Cryptoassets, Feedback and Final Guidance to CP 19/3, Policy Statement PS19/22 July 2019.

(24) See European Union above, page 31

(25) HM Treasury, UK regulatory approach to cryptoassets, stablecoins, and distributed ledger technology in financial markets: Response to the consultation and call for evidence, April 2022.

(26) The Investment Association, UK Fund Tokenisation: A Blueprint for Implementation, Interim Report from the Technology Working Group to the Asset Management Taskforce, November 2023.

(27) Digitisation Taskforce – Interim Report, July 2023.

(28) See Future of Finance, Digital Asset Custody Guide, Issue 2, Regulation Matters, pages 5 and 14.

(29) The protocols are still overseen by the non-profits World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), and the volunteer-run Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).

(30) Alastria, a non-profit, public permissioned national blockchain network funded by a consortium of large Spanish companies, but with academic and government involvement, is developing services of common interest such as digital identities.

(31) Franklin Allen, Antonio Fatas and Beatrice Weder di Mauro, “Was the ICO boom just a sideshow of the Bitcoin and Ether Momentum?,” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money, August 2022.

(32) BCG, The Tide Has Turned, Global Asset Management 2023 – 21st Edition, May 2023, Exhibits 1 and 2, pages 1 and 3.

(33) See Future of Finance, Digital Asset Custody Guide, Regulation Matters, pages 48-61.

(34) See separate article, “Reference data is the unlikely rocket fuel propelling us into a tokenised future” on pages 49 to 60.

(35) Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Second Edition, 1947, page 96.