European capital markets are inefficient, so why aren’t European CSDs doing more about it?

- Jan 5, 2024

- 24 min read

Updated: Jan 30, 2025

Article by Dominic Hobson, Co-Founder and Editorial Director at Future of Finance

Europe suffers from a surfeit of capital market infrastructures and especially an excess of CSDs. The fragmentation makes the European capital markets smaller and less liquid than they need to be, with negative consequences for the price of capital and economic innovation and growth. Despite a quarter century of regulatory efforts to force consolidation, the forces in favour of the status quo have prevailed, and in some ways strengthened their position. Even a direct ECB initiative (T2S), nearly 18 years after its conception, has yet to succeed in its narrow ambition of transforming settlement efficiency, which continues to be plagued by problems that would be familiar to the heads of operations of the 1990s. Yet it is hard to see how the current dispensation, especially in terms of ownership and incentives, can ever deliver a capital market infrastructure for Europe capable of providing more capital at keener prices to a wider range of European companies.

An infrastructure provides a common means to many ends. Road networks and electricity grids are the foundations on which market economies – and the astonishing variety of goods and services to which they give rise, all of them unforeseeable and unplanned – are built. Financial market infrastructures such as central securities depositories (CSDs) should play the same role in capital markets: provide the foundations for growth and innovation in finance.

In Europe, CSDs are not yet fulfilling this role. As the President of the European Central Bank (ECB) told the European Banking Congress on 17 November 2023, a quarter of a century on from the launch of the euro, the European capital market remains badly fragmented – and infrastructure shares a large part of the blame. “A truly European capital market needs consolidated market infrastructures,” Christine Lagarde told her audience.[1]

Europe has an overabundance of capital market infrastructures

Collectively, European equity markets are half of the size of their American equivalents. In Europe, the bond markets are a third the size of their American counterparts. The American securitised bond market – which is crucial to the ability of the American banking system to offer credit to the real economy – is three times the size of its European competitor. The American venture capital market is five times the size of its European equivalent.

Yet Europe has three times as many stock exchanges as the United States, and 20 times as many post-trade financial market infrastructures. There are 22 different stock exchange groups operating 36 different exchanges and 18 central counterparty clearing houses (CCPs) (see Table 1). 14 CCPs are currently authorised to offer services in the EU, and there is another ten operating on extended licences.[2]

Table 1

Capital market infrastructures

Source: New Financial, A New Vision for EU Capital Markets: Analysis of the State of Play and Growth Potential in EU Capital Markets, February 2022

True, multiple trading platforms and clearing houses are not incompatible with deep, liquid and sophisticated capital markets. Even the United States supports many exchanges and CCPs. The potential for fragmentation they create can be overcome by common regulators and regulations, insolvency regimes and a consolidated tape of prices and trading volumes. Such measures can integrate the pre-trading and trading components of a capital market – and the European Union (EU) has put them in hand.

A single European capital market needs a consolidated market infrastructure

But integration of multiple post-trade entities – CCPs and CSDs – is much harder to achieve by regulation alone. In fact, one reason why the United States hosts the deepest, lowest cost and most liquid capital market in the world – and therefore the one that is most attractive to investors in both equity and debt – is that it operates with a single CSD.

In Europe, by contrast, there are actually more CSDs in the euro area (22) than there are countries using the euro (20). The European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA) has 32 members and a further eight associate members, only two which (both Kazakhstani) are non-European. 85 per cent of its members are based in EU member-states or EU candidate-states.[3]

The United States – as Christine Lagarde argued in her speech – is the example European CSDs ought to follow. In 2022, the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) settled 957 million transactions worth US$462 trillion. By contrast, the six CSDs owned by Euroclear – the biggest CSD grouping in Europe – settled 138 million transactions worth €374 trillion (US$353 trillion).[4]

The comparison is even less flattering than these figures imply. Despite being owned by a single group, the six national CSDs owned by Euroclear continue to operate as domestic CSDs and maintain six separate memberships of ECSDA. The principal reason is their domestic client bases, and the political and bureaucratic support they enjoy at home. It is domestic clients, not cross-border clients, to which national CSDs in Europe are primarily responsive.

European resistance to consolidation is rooted in domestic markets and of longstanding

Domestic securities market clienteles – both broking intermediaries and their underlying institutional and retail buy-side customers – remain a major impediment to a meaningful consolidation of the CSDs of Europe. Domestic customers of national CSDs have no incentive to invest in the technologies and mergers necessary to build Christine Lagarde’s “truly European capital market” when they never invest outside their home market.

So when Christine Lagarde called on 17 November for the CSDs of Europe to “show [their] determination” and consolidate, she is ignoring the incentives they face. She is also ignoring history. More than 20 years have passed since the delivery of the Final Report of The Committee of Wise Men on the Regulation of European Securities Markets, chaired by the distinguished economist Alexandre Lamfalussy, president of the forerunner to the ECB (the European Monetary Institute) and father of the eponymous “Lamfalussy process” by which financial regulations are agreed within the EU.

The report, published in February 2001, stated explicitly that the development of European capital markets was being held up, inter alia, by “a large number of transaction and clearing and settlement systems that fragment liquidity and increase costs, especially for cross-border clearing and settlement.”[5]

The report added that the Committee was “convinced that further restructuring of clearing and settlement is necessary in the European Union” and , while it was content initially to let market forces decide the pace of restructuring, “if in in due course it emerged that the private sector was unable to deliver an efficient pan-European clearing and settlement system for the European Union, a clear public policy orientation would be needed to move forward.”[6]

Efforts to consolidate European capital market infrastructures started more than 20 years ago

Four initiatives were launched at the European level to bring this “restructuring” of post-trade market infrastructures into being. The first was a pair of reports prepared by a Group on Cross-border Clearing and Settlement Arrangements in the EU, in November 2001 and April 2003, based on consultation with the securities industry. Chaired by the Italian economist, Alberto Giovannini, the reports identified 15 technical, legal and tax barriers to efficient cross-border clearing and settlement of securities between national markets and made recommendations on how to clear them.

The second initiative was the updating of the 1993 Investment Services Directive (ISD), which introduced EU-wide “passports” for securities firms regulated in any one member-State. In 2007, the ISD was duly replaced by the first iteration of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFiD 1), which freed new entrants to compete with national stock exchange monopolies to trade shares. The competition MiFID 1 created in trading – the multilateral trading facilities (MTFs) Chi-X Europe and BATS Europe were its best-known creations – was expected to spread to post-trade services.

More directly for CSDs, MiFID 1 also freed securities firms licensed in any member-state to demand access to the clearing and settlement infrastructures of any other member-state. The legislation also obliged all regulated markets to designate which CSD they wanted to use to settle their transactions, creating the possibility that MTFs would disrupt the stock exchange stranglehold on clearing and settlement that obtained in most European marketplaces. In theory, these twin measures would put domestic CSD monopolies under pressure.

Charlie McCreevy, who took over as European Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services in 2004, just as the first drafts of MiFID 1 were beginning their journey through the EU legislative process, made making European cross-border clearing and settlement more efficient a priority of his term in office. By the time he stepped down in 2010, two further initiatives were under way to accelerate the consolidation of European clearing and settlement utilities.

The first was the introduction for all three types of securities market infrastructure – exchanges, CCPs and CSDs – of a Code of Conduct designed to intensify competition by imposing a combination of price transparency and open access. On 7 November 2006, the Federation of European Securities Exchanges (FESE), the European Association of Central Counterparty Clearing Houses (EACH) and the European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA) jointly signed a European Code of Conduct for Clearing and Settlement of cash equities.[7]

In it, the three trade associations committed themselves to freedom of choice of clearing and settlement services for firms trading equities, to be based on full transparency into the prices of the various services, and sufficient unbundling of services and inter-operability between systems to make such freedom of choice practicable as well as affordable. The idea was eventually to extend the provisions of the Code beyond equities to other asset classes.

By the time the Code of Conduct was signed the ECB had launched a fourth – and quite unexpected – initiative. On 7 July 2006 the ECB announced that its Governing Council had the previous day decided to explore, in cooperation with CSDs and other market participants, the establishment of a new service for securities settlement in the euro area, called TARGET2-Securities (T2S).

Efforts to encourage consolidation of European market infrastructures have failed for 20 years

The ECB announcement was seen at the time as a measure of the exasperation of the ECB with the slow progress made by European CSDs in consolidating post-trade market infrastructures. 18 years on, Christine Lagarde – who pointed out that “financial integration is lower than before the financial crisis” – can be congratulated for keeping her exasperation under control, for pitifully little has changed.

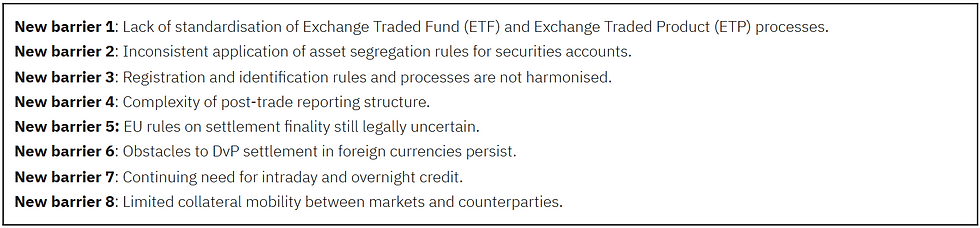

The Code of Conduct became a cipher, with CSDs issuing price schedules so complicated as to render them useless as a practical tool of business. As to the Giovannini barriers, a 2017 report by the European Post-Trade Forum (EPTF) – set up by the European Commission to undertake a broad review of the progress made in the field of securities post-trading and in the removal of Giovannini barriers – found only five had been resolved (see those marked in red in Table 2).

Table 2

The 15 Giovannini Barriers

Source: The Giovannini Group, Cross-Border Clearing and Settlement Arrangements in the European Union, Brussels, November 2001, pages 44-59.

While it is true that most of the ten Giovannini barriers that persist cannot be solved without government action, three (barriers 1, 3 and 8) could still be fixed by private sector action alone, so the failure of the Giovannini project is not just a public sector failure.

Worse still, the EPTF identified a further eight barriers to the integration of European capital markets (see Table 3) and another five issues to be closely monitored to ensure that they do not emerge as new barriers in the future (items the EPTF placed on a “watch list”). Even after making allowance for the fact that the EPTF simply reclassified some of the Giovannini barriers, the fact that a dozen barriers remain, more than 20 years on, is a measure of the failure to integrate European capital markets.

Table 3

New Barriers Identified by EPTF

The alternative to integration – Inter-operability between CSDs – has not advanced much either. When ECSDA reviewed links set up by its EU-based members in 2016, it found the average national CSD had eight-and-a-half. But many were to markets outside the EU, or indirect arrangements intermediated by sub-custodians or another CSD. A third did not offer delivery-versus-payment (DvP), obliging users to deliver securities without being confident of cash payment. Unsurprisingly, nearly half the links were used infrequently or not at all.[8]

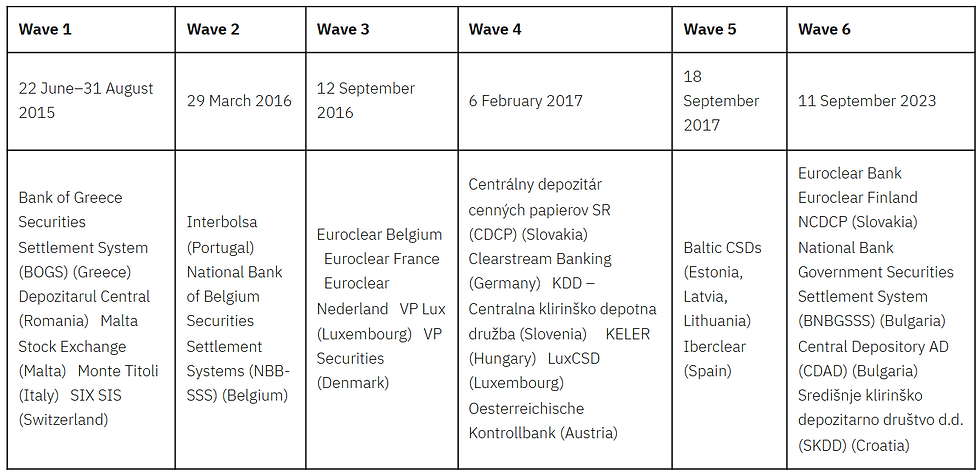

T2S took nearly a decade to start providing a service at all, and more than 17 years before the last CSDs to agree to join T2S managed to do so (see Table 4). Even now, euro area CSDs in Cyprus (Cyprus CSD) and mainland Greece (Hellenic Exchanges SA Holding, Clearing, Settlement and Registration (HELEX) remain outside T2S. The CSD to the largest stock market in Europe (Euroclear United Kingdom) never agreed to join at all.

Table 4

T2S Migration Waves 2015-2023

T2S has not succeeded in its central mission to make settlement more efficient

T2S had limited ambitions: it was designed to improve settlement efficiency only. A case can be made that it has not solved even that. Hopes that T2S would yield lower settlement fees and savings on cash and collateral tied up in inefficient settlement processes, have proved to be vain.

Far from falling, the slow migration of CSD settlement volumes to T2S meant the basic DvP fee had to be increased from €0.15 per instruction to €0.195 per instruction, plus a temporary surcharge of €0.04 per instruction from 1 January 2019. When announcing the price increase in June 2018, the ECB announced T2S would not generate revenue, as opposed to covering its costs, for another 14½ years.[9] At the end of 2022, T2S still owed the ECB €458.1 million in development costs it had yet to repay.[10]

The European settlement process is not just more expensive than promised. It is still clumsy, with duplicated solutions, fragmented processes, and unnecessary risk and cost inefficiencies when transactions are settled across borders. The origins of this lie in the initially narrow focus of T2S on settlement, which left asset-servicing in the control of the local sub-custodian banks. Predictably, they have maintained their longstanding model of intermediating access to CSDs in T2S markets.

T2S has not boosted cross-border transactional traffic either. Cross-CSD settlements as a proportion of total settlements by volume amounted to just 1.25 per cent in 2022, not least because CSDs started charging extra for cross-CSD settlements.

This is a measurable failure for a project that aimed to make cross-border settlement more efficient. Part-effect and part-cause is that local exceptions have survived, even in the basic settlement process, where T2S failed to impose standards, but especially in the more complex asset servicing areas such as corporate actions, tax reclaims and proxy voting.

The remaining 98.75 per cent of settlements that do not have to cross between CSDs remain subject to a worrying degree of failure. In terms of transactions settled at the end of the trading day by both value and volume, settlement efficiency has declined every year since the ECB started measuring it on the present basis (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

Source: European Central Bank, T2S Annual Reports 2020 and 2022

In 2022, over one million cash penalties per month – which are administered by the CSDs – were issued for failed settlement instructions under the Settlement Discipline Regime (SDR) introduced on 1 February 2022 by the terms of the Central Securities Depositories Regulation (CSDR).[11] At an average value of €145, that amounts to €1.7 billion in penalties over the 11 months.

Though €1.7 billion is in aggregate a large number, it proves that at the counterparty level cash penalties are treated as trivial by market participants: they know they can afford to let trades fail. The one measure which would undoubtedly have persuaded them otherwise is mandatory buy-ins, by which any failure by a seller to deliver can be remedied by the buyer purchasing the security from a third party and passing any additional costs the purchase entails back to the seller.

However, ferocious lobbying by the European securities industry saw buy-ins withdrawn from the SDR sine die. Unlike cash penalties, European CSDs (which possess the information about failed settlements) made clear from the outset that they wanted to play no part in administering buy-ins beyond sharing information about fails because of the potential impact on their risk profile. This decision deprived European regulators of any means of implementing buy-ins that was not dependent on the counterparties affected.[12]

Credit costs are rising and collateral mobility inefficiencies persist

In addition to the cash penalties, settlement fails also increase demand for credit, which is getting more expensive as interest rates rise. The daily average value of unsettled transactions in T2S in 2022 ranged between €25.24 billion in August and €36.28 billion in September, significantly higher than the 2021 range of €14.75 billion in August and €34.52 billion in November.

If the average daily value of unsettled transactions in T2S is currently, say, €30 billion, at a time when the ECB overnight credit rate has risen from a low of 0.25 per cent in the Spring of 2022 to 4.75 per cent from September 2023, that implies an increase in T2S-wide borrowing costs from €75 million to €1.425 billion just to settle trades at the end of the day.

Credit is not available without collateral. Were it not for the unwinding of the post-financial crisis support supplied by central banks, and the associated return of central bank-eligible securities to the market, the eurozone might be facing another collateral squeeze. Its absence is just as well, given the continuing fragmentation of the European collateral market, with multiple CSDs unable between them to execute collateral transfers across borders in real-time.

Instead, market participants rely on moving assets between custodian banks, which amplifies settlement risk, devours intra-day liquidity and requires banks to maintain costly buffers of cash and securities in multiple markets. HQLAx – the blockchain-based collateral platform developed by Deutsche Borse, R3 and a group of banks to tackle these inefficiencies – estimates that inefficient collateral management can cost a Tier 1 bank €50-100 million a year.

True, T2S has an auto-collateralisation mechanism, by which T2S accountholders without sufficient funds to settle trades can obtain credit from their local central bank. In 2022, use of auto-collateralisation averaged €123.90 billion a day, up from €115.79 billion in 2021. The Eurosystem Collateral Management System (ECMS), designed to replace the 20 different national central bank collateral management systems with one unified system, is not scheduled to start until November 2024 – about seven years after work on it first began.

The sources of settlement inefficiency are not new

In November 2023 ECSDA published a review of settlement efficiency in Europe, attributing the faltering performance visible in Chart 1 to market volatility, sanctions on Russia and Russians and to exaggerations of the scale of the problem caused by weaknesses in the statistical methods used by the ECB to measure efficiency.

But the report also cited sources of inefficiency that would be familiar to heads of operations 40 years ago: basic operational errors, lack of securities to deliver, late matching of trades, and poor-quality reference data (such as Standing Settlement Instructions (SSIs)) and other information needed to settle trades.[13] It is telling that a blockchain-based platform (SSImple) has been set up to use new technology to address age-old settlement problems.[14]

The deterioration in T2S settlement performance, and the ditching of mandatory buy-ins as the only effective remedy, is also occurring at a critical time. European regulators are considering a reduction in the settlement timetable from the current trade date plus two days (T+2) to T+1.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has already adopted a T+1 timetable, and Canada and Mexico have followed suit. The accelerated settlement cycle will start on 27 May 2024 in the Canadian and Mexican markets and on 28 May 2024 in the United States.

It will be difficult for Europe not to follow the North American example, especially since China and India are there already. With one day less to settle trades, the European market is likely to see a further increase in settlement fails – unless it undertakes a set of reforms that are more ambitious than the mix of workarounds (securities lending, partial settlements) and the intensification of the unending search for better quality reference data that are recommended as solutions in the ECSDA report of November 2023.

The long-term solution to settlement inefficiency is obvious but cannot overcome entrenched interests

The obvious solution is consolidation. After all, the reason why post-trade infrastructure in Europe has had such a painful journey, with T2S under-achieving even on its limited goals, is that Europe still lacks the equivalent of the DTCC: a single custody and settlement system.

At the turn of the century a DTCC for Europe was what the (mainly American) investment banks wanted, starting with a merger of the two international CSDs (ICSDs) – Brussels-based Euroclear and Luxembourg-based Clearstream – whose business those same investment banks utterly dominated.

It did not happen. Instead, Clearstream escaped the clutches of its larger rival across the Ardennes by selling itself to Deutsche Börse in two stages (2000 and 2002). To this acquisition the German stock exchange later added the German domestic CSD (also in 2002).

Euroclear, meanwhile, absorbed the domestic CSDs of France (February 2001), Belgium and the Netherlands (June 2001) and the United Kingdom (July 2002). It later took over the CSDs of Finland and Sweden as well (October 2008).

These moves sparked a debate about the respective merits of vertical integration (in which CSDs would merge with stock exchanges) and horizontal integration (in which CSDs would merge with each other).

In theory, horizontal integration was best for market participants, because it would cut the costs of moving cash and securities between CSDs across national borders to settle trades on exchanges that competed for trading activity. But in reality most CSDs in Europe settle trades between domestic counterparties on the domestic exchange, making vertical integration the better outcome for most service providers.

These opposing views mirrored exactly the conflict between the vision of the ECB and the European regulators (a single European capital market) and the interests of both the national CSDs and their principal users and gatekeepers (the domestic custodian and international sub-custodian banks).

The sub-custodian banks understood that a single European CSD, or even a multi-market CSD in Europe, posed an existential competitive threat. They could never match its economies of scale, not just in basic settlement and asset-servicing, but in higher margin areas such as collateral management, especially if they had a banking licence (which Euroclear and Clearstream did).

Understandably, the managements of the national CSDs also saw absorption into a larger entity as a disagreeable alternative to continued independence. Importantly, they could count on their domestic clienteles to support their resistance, since any alteration to the status quo imposed on domestic brokers and investors a set of connection costs for a service (cross-border trading and settlement) that most of them would never use.

A majority of European CSDs are controlled by stock exchanges, making consolidation difficult

It is hard to see how consolidation of CSDs can be revived now. Within the eurozone, vertical ownership abounds, with 60 per cent of CSDs controlled by stock exchanges. Deutsche Börse owns three CSDs. Euronext owns four. In May 2007, when NASDAQ purchased the Nordic stock exchange group OMX, it also acquired the CSDs of Estonia, Iceland, Latvia and Lithuania. In June 2020 SIX acquired the Spanish CSD as part of its purchase of acquisition of Bolsas y Mercados Españoles (BME), the operator of the Spanish stock exchanges.

Of the 32 full-time members of ECSDA, stock exchanges also control 60 per cent. Of the remainder, a quarter are owned by shareholders that might be willing to sell, though the outcome is distorted by Euroclear. The Brussels-based ICSD accounts for 80-90 per cent of the European CSDs that are controlled by neither a stock exchange nor banks – and even Euroclear is 22.6 per cent owned by banks (14.29 per cent) plus Euronext (3.34 per cent) and London Stock Exchange (4.92 per cent).

Euroclear, which has been the subject of sale speculation for years, certainly has the most mixed shareholder group of any CSD in Europe. Even if it was sold to an acquisitive buyer, the new owners of Euroclear would almost certainly find that no CSDs in Europe were available to buy. Stock exchanges, which capture more trading business by controlling settlement as well and which can make more money from operations than trading, are not willing sellers.

Even if they were, their domestic clients would resist, so even consolidation of CSDs as a by-product of stock exchange consolidation seems improbable. Although banks control some of the stock exchange groups in Europe, they have shown limited capacity to create pan-European banking groups even in their core business, let alone demonstrate an ability to drive infrastructural consolidation.

So, as a route to an integrated European capital market infrastructure consolidation through private sector mergers looks like a lost cause. The classic consolidation process – in which larger groups emerge and add scale by buying smaller entities, ending with an oligopoly in which the top three or four performers control 80-90 per cent of the market – is unlikely to occur in the European stock exchange or CSD or banking industries.

Consolidation will have to come from outside the CSDs rather than from within the CSDs

If Christine Lagarde’s call on 17 November 2023 – echoing the Wise Men of 2001 – for the “private sector to show its determination” and drive the consolidation of CSDs is to be realised, a different type of private sector actor is almost certainly necessary. In short, the consolidation of European CSDs will probably have to be realised by outside forces competing successfully with the incumbents.

Here, public policy is powerless to help. True, MiFID I, implemented in November 2007, did empower competitors to the established stock exchanges, and the new MTFs lowered the revenues and profits of the incumbents and thereby reduced the costs incurred by issuers and investors. Despite allegations that it fragmented liquidity, MiFID 1 did achieve tighter integration of capital markets at the trading level. But it also increased rather than decreased the number of issuance and trading platforms.

Despite two “action plans” launched by the European Commission to realise a Capital Markets Union (CMU) or single capital market for Europe – a goal first adopted in July 2014, with a target date of end-2019 – the Europe-wide real economy remains (thanks to Brexit) more dependent than ever on bank loans rather than capital markets. As Christine Lagarde argued in her 17 November 2023 speech, the European capital market is going backwards: “Financial integration is lower than before the crisis.” [15]

She is not wrong. Cross-border issuance of securities is nugatory. The daily average volume of cross-CSD settlement transactions averaged 1.15 per cent of total T2S settlement volume in 2021-22, while the daily average value of cross-CSD settlement transactions represented an average of 3.37 per cent of total T2S settlement value in 2021-22.[16] Holdings via CSD links are static at around a fifth of securities outstanding.[17]

Largarde argued that the CMU will continue to fail unless the EU overcomes the persistence of regulation at the national level and empowers a pan-EU financial services regulator to drive change: writing and then enforcing a single European capital markets rule book and imposing a consolidated tape (a digital system that collates real-time price and volume from exchanges and disseminates it to investors).

But Lagarde also signalled clearly that CSD consolidation is essential. So far, incumbent CSDs have succeeded magnificently in maintaining the status quo. Since the financial crisis of 2007-08, only one European CSD (Iberclear) has merged into the same group as another – and that was a by-product of a stock exchange acquisition by a group based outside the EU, let alone the eurozone, looking primarily to increase its own size rather than solve the infrastructural shortcomings of Europe.

Part of the secret of the current stasis is the success of the incumbents at suppressing new entrants. Any market participants minded to use the services of novel competitors are soon dissuaded by the knowledge that they will forgo convenient access to the counterparties the incumbents service. This brute reality outweighs the theoretical freedoms bestowed on intermediaries by MiFID 1 (which freed securities firms to demand access to any CSD) and on issuers by CSDR (which freed issuers to choose any CSD).

In 2013, two major global custodian banks – J.P. Morgan, in conjunction with London Stock Exchange Group, which then owned the Italian CSD Monte Titoli, and BNY Mellon – tried to capitalise on T2S by setting up CSDs of their own. Both had to be abandoned. In 2018, VP Securities, the Danish CSD, closed VP Lux, its Luxembourg CSD. ID2S, which provided blockchain-based CSD services to holders of money market instruments in France, was forced to close in October 2021 after just two-and-a-half years.[18]

CSDs have adopted a cautious approach to the technological revolution

Likewise, new technologies that offer pathways to greater efficiency, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain, are not embraced with conspicuous enthusiasm by European CSDs. When the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) surveyed European CSDs on their use of “FinTech” in 2021, it found some were using AI but use of blockchain was “extremely limited,” with just one CSD enthusiastic about it, and none supporting “crypto-assets.”

ESMA also found that the majority of CSDs made no use of regulatory sandboxes to experiment with new technologies and that most were reluctant to adopt new technologies without clear guidelines from regulators, a strong appetite from users and sufficient experience from proofs of concept and pilot tests to warrant investment.[19]

In 2017 it was not a CSD but Euronext, in conjunction with BNP Paribas, CACEIS, Caisse des Dépôts, Euroclear, Euronext, S2iEM and Société Générale – and with the support of Paris EUROPLACE – that launched the LiquidShare fintech to provide a blockchain-based post-trade infrastructure for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Yet SMEs are an obvious new business target for any CSD.

Investment in blockchain technologies is largely confined to the international CSDs. Both SIX in Switzerland and Clearstream in Germany have embraced blockchain and used local regulatory and legislative accommodations to launch experiments in issuing and settling asset-backed securities tokens, including through the establishment of digital asset CSDs.[20]

Clearstream has also acted as midwife to the HQLAx blockchain-based collateral mobility platform and the FundsDLT mutual fund tokenisation platform, which parent company Deutsche Börse acquired in toto in August 2023.[21] Euroclear invested in a bond market start-up (Algomi) and later launched Digital Securities Issuance (D-SI) service which the World Bank has used to issue digital securities.[22]

Where the EU has sought to encourage experiments in the use of blockchain technology, via the DLT Pilot Regime, which came into effect on 23 March 2023, CSDs have not responded as positively as might be expected. After all, the specific purpose of the Pilot Regime is to allow operators of financial market infrastructures (including CSDs) to test blockchain technology in the issuance, trading and settlement of tokenised equity, debt and fund instruments (derivatives are excluded) without breaching the obligations laid on incumbents under MiFID and CSDR (notably the requirement imposed on CSDs under CSDR to settle transactions in central bank money).

The EU Pilot Regime protects rather than inspires the CSDs of Europe

The Pilot Regime also has a distinct bias towards regulated entities such as CSDs. Any unauthorised new entrants must apply simultaneously for a MiFID or CSDR licence. Applicants of both kinds must apply only for exemptions from regulations which would otherwise prevent them conducting the tokenised securities.

Despite these attractions, no established CSD has submitted an application to experiment via the Pilot Regime. While it is true that the low ceilings on size set by the Pilot Regime exclude most of the issuance and asset-servicing business of the major corporations, banks and asset managers that traditional CSDs look after, this also protects the CSDs from competition, and in more ways than one.

Under the Pilot Regime, tokenised shares are restricted to issuers with a market capitalisation of up to €500 million; debt instruments to issuances of up to €1 billion; and funds to assets under management totals no greater than €500 million. Better still for established CSDs, the asset class ceilings are also subject to an aggregate value threshold of €6 billion – and if the aggregate value exceeds €9 billion, the market infrastructure must “transition” to the traditional CSD model.

The risk of “transition” obviously benefits established CSDs running a traditional CSD business already. But, far from inspiring established CSDs to set up experimental blockchain-based platforms, it has freed traditional CSDs to wait for any successful pioneers without a traditional business to get in touch to rescue them from their own success.

Indeed, the Pilot Regime obliges applicants that do not have an in-house solution to put transition arrangements in place with a traditional provider within five years of permission to operate being granted – so experimenters will need to get in touch promptly. Coupled with the onerous application process, the uncertain duration of the Pilot Regime and liability for investor losses, it is not hard to see why the scheme is not a success in creating innovative rivals to incumbent CSDs or driving innovation at established CSDs.

The “Digital Securities Sandbox” in the United Kingdom to be run by the Bank of England and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) could scarcely be less enticing than the Pilot Regime, and it is not. The United Kingdom government, which decided not to publish ceilings, has already made clear that it will be more accommodating on questions of size and transitioning.[23]

The statutory instrument that implements the Sandbox in law was laid before the United Kingdom Parliament on 18 December 2023, so applicants can apply once the regulations come into force on 8 January 2024.[24] But it would be surprising if an established European CSD used the opportunity to experiment with blockchain-based services – after all, even if one did, it would not be licensed to provide services within the EU.

Neither the CSDs themselves nor their potential competitors can effect meaningful change

In fact, it is already clear that the overwhelming majority of European CSDs have concluded that blockchain technologies have yet to offer a persuasive business case or pose a serious competitive threat. CSDs have more immediate incentive to spend time and money fixing quotidian operational pain-points than building future-proof infrastructures.

Which leads to a melancholy conclusion. This is that the possibility of consolidation of European CSDs ultimately reduces to a single question – can a technology-based challenger win sufficient business away from the incumbents to build a single CSD? – whose answer depends on primarily on whether tokenisation of securities and funds takes off or does not take off.

At the moment, the token markets are trivial in terms of scale. And as long as blockchain protocols struggle to inter-operate and central bank money – indeed, any form of trustworthy and stable cash – remains unavailable on blockchain networks, incumbent CSDs can be confident the vast majority of the issuers and investors they service today will not bother with tokenisation.

Regulators, despite impressions to the contrary given by the President of the ECB and the Pilot Regime, are unlikely to worry them overmuch either. Montis Digital, the digital securities CSD set up by the London-based digital securities exchange Archax in September 2021 precisely because no existing CSD could meet the needs of the exchange, is still awaiting the outcome of its submission for a full EU operating licence in Luxembourg. The potential innovators and consolidators of the future are likely to run out of money before the regulators run out of time.

The uncomfortable truth is that it is hard to see how the current post-trade dispensation can ever contribute to the creation of a single European capital market. This stasis will exact its price. New Financial has estimated that a single European capital market would more than double the size of the European IPO, corporate bond and pension fund markets and nearly double the value of European venture capital and stock markets.[25] The potential gains it itemises add up to nearly €32 trillion – or getting on for half the €73.7 trillion 40 European CSDs held in custody at the end of 2021.[26] The opportunity cost of the current stand-off is high.

Join us on February 22ndn at 2pm UK time for our webinar ‘In Europe needs a single European CSD, who will build it?’

[1] “A Kantian shift for the capital markets union,” speech by Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, at the European Banking Congress, Frankfurt am Main, 17 November 2023, page 5.

[4] Euroclear Annual Review 2022, pages 20-21.

[5] Final Report of The Committee of Wise Men on the Regulation of European Securities Markets, Brussels, 15 February 2001, page 10.

[6] Final Report of The Committee of Wise Men on the Regulation of European Securities Markets, Brussels, 15 February 2001, page 16.

[7] The Federation of European Securities Exchanges (FESE), the European Association of CCP Clearing Houses (EACH) and the European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA), European Code of Conduct for Clearing and Settlement, 7 November 2006.

[8] European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA), Overview of CSD Links, 29 July 2016.

[10] T2S financial statements for the fiscal year 2022, May 2023, Note 8, page 7.

[11] The CSDR came into force on 17 September 2014, but its requirements were implemented over several years. For example, the switch in European markets from settling securities transactions on T+3 to T+2 took place in 2014 but the SDR did not start until February 2022.

[12] Their preferred option was for buy-ins to be managed by the trading counterparties. See European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA), The Operation of the Buy-in Process under the CSD Regulation, 6 August 2015.

[13] European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA), Settlement efficiency considerations, November 2023.

[15] “A Kantian shift for the capital markets union,” speech by Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, at the European Banking Congress, Frankfurt am Main, 17 November 2023, page 3.

[16] European Central Bank, TARGET2-Securities Annual Report 2022, page 27.

[17] Eurofi Regulatory Update, April 2023, footnote 24, page 37.

[18] See https://futureoffinance.biz/what-i-learned-from-managing-the-first-blockchain-csd-in-europe/

[19] European Securities and Markets Authority, Report to the European Commission: Use of FinTech by CSDs, 2 August 2021, pages 10-15.

[20] For a full discussion of the German initiative, see the second edition of the Future of Finance Digital Aset Custody Guide (DACG2), pages 31-43 at https://futureoffinance.biz/digital-asset-custody-regulation-matters-2/

[21] Clearstream press release, Deutsche Börse acquires outstanding shares of leading digitised fund distribution platform FundsDLT, 3 August 2023.

[22] Euroclear press release, Euroclear launches DLT solution for the issuance of digital securities, 24 October 2023.

[23] HM Treasury, Digital Securities Sandbox: Response to consultation, Novembre 2023.

[25] New Financial, A New Vison for EU Capital Markets: Analysis of thre State of Play an Growth POtentila in EU Capital Markets, February 2022, Appendix II, page 32.