Is tokenisation of securities markets the nemesis or the apotheosis of the CSD?

- Jan 1, 2022

- 28 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2025

Both AMEDA and the Future of Finance are grateful to Percival for making today’s discussion possible.

In 1997 Steve Jobs famously returned to Apple, the company he had founded 20 years earlier.

The company was on the brink of bankruptcy.

Its market share was falling.

Its innovations were failing.

Asked what he would do to save the company, Jobs gave an answer worthy of Zhou Enlai’s assessment of the French Revolution.

“I’m going to wait for the next big thing.”

The Next Big Thing turned out not to be the shiny new Mac he is holding in this photograph but this, the iPod.

The iPod, as we know, evolved into the first smartphone, the iPhone.

The corporations that in 2007 dominated the music industry (Polygram, Universal, Sony), the mobile telephone industry (Nokia, BlackBerry) and the computer industry (Microsoft, Compaq) all failed, unlike Steve Jobs, to anticipate The Next Big Thing.

But the most organisations are not set up to do that.

They have annual budget cycles.

Cost-cutting programmes.

And a deeply ingrained tendency to assume that next year will be the same as this year, plus 5 per cent.

What Steve Jobs did instead was notice a change in the music industry caused by the Internet plus the MP3 file format.

And not just notice it – but exploit it with great skill and speed and determination.

I don’t know whether Blockchain represent a comparable change in the ambient technological environment of the securities industry.

But I do know that it is a development that Central Securities Depositories (CSDs) would be unwise to ignore.

At present the securities value chain works by moving data between different systems operated by the various intermediaries: exchanges, brokers, asset managers, asset owners, custodian banks, central counterparty clearing houses, order matching utilities and CSDs.

CSDs play a crucial role at several points in the chain.

Issuance.

Confirmation.

Settlement.

Registration.

Custody.

Asset servicing.

Securities lending.

Collateral management.

In tokenised securities markets, it is not data that moves, but the assets themselves.

From the digital wallet of the issuer into the digital wallets of the investors.

From the digital wallet of the sellers to the digital wallets of the buyers.

From the digital wallets of the lenders to the digital wallets of the borrowers.

Tokenised cash against tokenised securities.

Each transaction updating the register automatically as it settles.

While the smart contacts embedded in the assets automate the servicing of the assets.

So all these functions:

Issuance.

Confirmation.

Settlement.

Registration.

Custody.

Asset servicing.

Securities lending.

Collateral management.

Are gone.

The occupation of the CSDs is gone.

Now, if this happens, there are three possible outcomes for CSDs.

The first is that tokenisation disintermediates the CSDs – there is literally nothing useful left for them to do.

The second possibility is that CSDs are disrupted.

But they find a new role or roles to play.

There is a third possibility.

This is that CSDs become the arbiters of the development of the tokenised securities markets.

In other words, tokenisation will not destroy the CSDs, but rejuvenate them.

I will come back to this possibility later.

A more immediate question is, `Why bother to do anything at all?’

Because at the moment the securities token markets are small

In fact, they are so small we do not really know how small they are.

There is no reliable source of data for something which matter as little as security tokens do.

My guess is that the total value of all security token issues outstanding today is maybe US$50 billion.

It is a generous estimate.

But it is still means that the combined value of the conventional equity, bond and funds markets of today is more than 6,000 times as high.

Even the crypto-currency markets are almost 40 times more valuable.

Then there are the shortcomings of the Blockchain technology itself.

It is not fast.

It is not scalable.

And it is not private.

No wonder even those financial institutions most enthusiastic about making use of the technology have had to keep much of the work and most of the data off the blockchain itself.

That suits regulated institutions, which prefer closed networks and data confidentiality.

Would regulators want anything else?

Here in Europe the regulators insist that tokens are issued into CSDs; and are settled in CSDs; and that any CSD that does not want to do that must stay small.

*

So there are good reasons for doing nothing.

The token market is tiny.

The technology is primitive.

And the regulated institutions and the regulators will protect you.

But doing nothing is almost certainly a mistake.

After all, if tokenisation takes off, it could disintermediate the CSDs that do nothing.

But it could also transform the fortunes of the CSDs which do something.

On a global scale, if tokenisation took just a 5 per cent share of that US$300 billion invested in the global bond, equity market and fund markets, it would be a US$15 trillion market.

So CSDs should have a bias to action.

*

The first question is what action to take.

And the second question is when to act.

In practice, these questions are inseparable: to act is to do.

The questions – when? and what? – are also unanswerable

Because the future is unknowable.

The future always is.

But there is a way of thinking about it.

This is to divide the future into the short term, the medium term and the long.

And to take action not precipitously, but incrementally.

In the short term – say, to five years out, 2027 – do the minimum.

Build a prototype, issue tokens on to it, and see if they can be settled and safekept on and off a blockchain.

By the medium term – say, to ten years out, 2032 – the environment will be getting less comfortable.

The volume of security tokens issued is likely to have grown significantly.

Legal and regulatory frameworks will have adapted to tokenisation.

Tokens will be trading alongside conventional securities, but most new issues will be in tokenised form.

What to do then?

Build or buy the capability to service token issuers and investors, alongside conventional security issuers and investors – and enable them to switch between the different networks.

In the long-term – say, 15 to 20 years out, 2037 or 2042 – the transition to tokenised forms of issuance and trading is likely to be substantially complete.

New issues will be almost all in tokenised form.

At that point, the successful CSD will probably have built or bought a fully integrated tokenisation platform that allows tokens to be issued, traded, settled and safekept as parts of single digital process.

Incremental investment of this kind contains the cost, and the risk.

If tokenisation fails to happen, as it might, the investment can be switched off as soon as that becomes obvious.

Incremental investment, in other words, is a low-cost way of hedging the risk that security token markets will take off.

*

But what do we mean by “security tokens”?

In principle, any asset is capable of being tokenised.

There are a dozen separate asset classes on this chart.

Between them, they add up to more than US$425 trillion.

Not just securities and funds but real estate, oil, infrastructure, diamonds, gold, wheat.

We could add fine art, fine wines, classic cars, wristwatches.

All these assets are being tokenised, already.

The US$40 billion that has gone into the Non-Fungible Tokens (or NFTs) is just one example of what is happening.

It is tempting to see NFTs as a latter-day equivalent of Tulip Mania.

A festival of money launderers.

Or a way for professional traders to separate the gullible from their cash.

The NFT market is all of those things.

But look also at what NFTs are pioneering.

Asset class expansion.

Transferability.

Distribution of entitlements.

Network-building.

Cross-selling opportunities.

Royalties payable to originators.

All of those things point to a market whose growth can be sustained.

The principal opportunity for CSDs is the provision of secure digital wallets to holders of NFTs and other asset-backed tokens.

At least one CSD (NSD in Russia) has experimented already with tokenised grain warehouse receipts.

Another (Clearstream) is developing a service to support the tokenisation of fine art.

Both markets are nascent at best.

But history shows that new financial markets can scale astonishingly quickly.

Today, the mortgage-backed securities market in the United States has more than US$12 trillion in bonds outstanding.

The average trading volume is nearly US$300 billion a day.

But in 1970 it did not exist.

Or take money market funds.

The first money market fund was not invented until 1971.

Yet today money market funds have total holdings of more than US$5 trillion.

Or take index funds.

These too were invented in the 1970s.

They got nowhere for 20 years.

Today, they account for more than a fifth of global assets under management, or US$22 trillion.

When the International Securities Services Association (ISSA) surveyed asset managers and asset owners in 2021, it concluded portfolio allocations to digital assets will hit 1-2 per cent in the next year or two.

That does not sound like much, but the global asset management industry is running US$103 trillion in Assets under Management (AuM).

1-2 per cent of that is US$1-2 trillion.

If the security token market grew at, say, 35 per cent a year over the next 20 years, it will be a US$20 trillion market by 2042.

That represents a serious risk for CSDs that choose to do nothing.

Why?

Because somebody has to do the work of supporting that US$20 trillion.

And if it is not CSDs, it will be somebody else.

Competitors are emerging already.

Our latest count at Future of Finance found more than 80 entities looking to provide custody services to institutional investors.

An incredibly complex eco-system, characterised by mergers and acquisitions as well as partnerships, is evolving.

There are dozens of digital wallet providers.

And digital custody technology vendors.

Crypto-currency exchanges (such as Coinbase) provide regulated, independent custody services.

Token exchanges are already working with independent custodian banks to safekeep uninvested cash.

One of them – Archax, the regulated crypto-currency and token exchange in London – is actually building its own regulated CSD to enable security tokens to be registered and settled (Montis).

Two other CSDs (SDX in Switzerland and Clearstream in Frankfurt) have built token CSDs.

Why?

Because no existing CSD is able to provide security token services.

This is the risk: if specialist CSDs become entrenched before the established CSDs are able to respond, the opportunity for CSDs to support the growth of the security token markets will be lost.

They will simply be bypassed.

And if security token markets are growing, security markets are not.

Publicly tradeable equities are shrinking.

The OECD estimated in June 2021 that since 2005 30,000 companies had de-listed from stock exchanges around the world.

That number is equivalent to three quarters of all listed stocks today.

And the losses are not being offset by new listings.

For CSDs, whose core business is to issue, register, settle and safekeep publicly tradeable securities, that is what you call an adverse secular trend.

CSDs could find themselves being squeezed between shrinking traditional revenues on the one hand and a failure to seize security token revenues on the other.

*

It gets worse.

Tokenisation is going to squeeze the revenues of the customers of the customers of the CSDs.

By which I mean the buy-side.

When ISSA surveyed asset managers and asset owners in 2021, it found one in seven was investing in securities tokens already, and up to two in five expected to do so within two years.

Why?

Was it to diversify their portfolios?

No, it was to lower their costs.

That will put the most important customers of the CSDs – namely, the custodian banks – under pressure.

Custodians work with issuers as well.

And they too want to tokenise to cut the cost of raising capital.

Where will those lower costs come from?

From the automation of the work of the entities that stand between issuers and investors.

Or what is known as “disintermediation.”

In securities, intermediaries at risk include:

Investment banks that structure issues;

Lawyers that draft documents;

Exchanges that list securities;

Paying agents that distribute entitlements;

Broker-dealers that broke and trade securities;

Clearing brokers;

Clearing houses;

Custodian banks; and of course …

CSDs.

In the funds markets, intermediaries at risk include:

Transfer agents and

Order routing networks

Now, practice may depart from theory.

Both surveys and anecdotes indicate investors value intermediaries, and especially independent custodians and CSDs to safekeep and service their tokens.

And it is not as if CSDs and custodian charge a lot in the first place: the room for economies is small.

But even if nobody in this value chain is actually disintermediated, tokenisation will still squeeze the profitability of all intermediaries.

Finance is a business that enjoys margins that are two to four times as fat as the economy-wide average.

To maintain those margins, finance is going to have to raise its productivity.

There is only one way to raise productivity.

It is by innovation.

At forward-looking CSDs, this is now happening.

When ISSA surveyed the sell-side and the buy-side last year, it found the number of respondents exploring blockchain-based applications had tripled since the previous year; that the number with live applications had doubled; and that the value of the resources deployed were up by a third.

Look at the four asset classes on the right-hand side of this chart.

Asset managers and asset owners are investing in the tokenisation of equities, mutual funds and bonds, in that order.

Their service providers, which include CSDs, are investing in the tokenisation of fixed income, equities, unlisted securities and mutual funds – in that order.

There is a mismatch – and it is an interesting one – in unlisted securities.

But the buy- and sell-side are in other ways almost perfectly matched.

In other words, token investments are already aiming at the core businesses of the average CSD: Equities, Fixed Income and Funds.

Take equities.

Equities pioneered tokenisation.

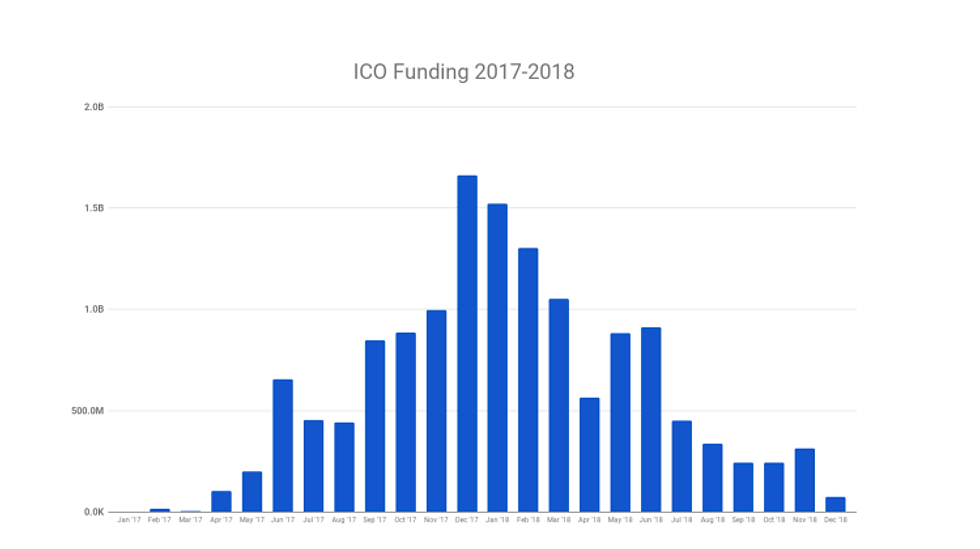

The Initial Coin Offering (ICO) boom of 2017-18 was not really about coins at all.

More than US$19 billion was raised in just two years in the form of tokenised equity to build platforms, business services software and banking applications.

The ICO boom has in effect continued in the Decentralised Finance (DeFi) markets, which are currently worth US$60 billion but have ranged as high as US$100 billion.

However, ICOs and DeFi have proved unhelpful in encouraging equity tokenisation.

Many ICOs were scams.

The money was stolen, by insiders or by hackers.

And regulators rightly deemed them to be issues not of coins but of securities.

DeFi today remains a retail market characterised by a mixture of obscurity, opacity and volatility.

The experiments are undeniably interesting and will one day be useful.

But mainstream institutional issuers and investors are not going to touch DeFi until it can offer much higher standards in terms of counterparty due diligence, safe custody and cyber-security.

KYC checks, safe custody, cyber-security – these are precisely the benefits that CSDs can bring to the DeFi markets.

After all, institutional money is at present proving reluctant to invest even in equity tokens that are issued on to regulated exchanges.

In fact, it says everything about the current state of the equity token markets that the biggest cryptocurrency exchange in the world, Coinbase, was so unconvinced of the value of equity tokens that it opted in April 2021 to list its own shares on Nasdaq via a conventional Initial Public Offering (IPO) instead.

That said, it would be foolish for CSDs to relax.

Regulated token exchanges are proliferating.

The SEC has approved a public offering of an equity token.

So equity tokens are not not happening.

But, as Coinbase proved, there is no good reason yet for issuers to believe that equity tokens are a better option than conventional equity markets.

The current opportunity in equities probably lies in unlisted shares.

The “Pink Sheets” market in the United States, for example, is big.

It turns over US$200 billion a year.

But the market is also notoriously opaque and illiquid, and stock prices are heavily manipulated.

Tokenisation could fix that.

The respondents to the ISSA survey certainly think so.

Unlisted securities are a priority for 45 per cent of the securities services industry respondents.

Unfortunately, as this Chart also shows, asset managers were a lot less enthusiastic.

Probably because they – or at least their institutional clients – are less able to buy unlisted securities.

That is precisely the sort of barrier which tokenisation, by providing unlisted securities in regulated form, can clear.

But a lack of interest at this point on the buy-side is undeniably a problem.

In the short term, it is probably safer to assume that equities will not tokenise as fast or on such a scale as bonds.

*

The global bond markets are big (US$123½ trillion).

Heavily intermediated (by CSDs as well as investment banks and custodian banks and paying agents).

And inefficient, especially in the primary market, where a horde of well-funded FinTechs is gathering to wean the industry off spreadsheets and email.

Experiments have proved that issuing bonds on to blockchains works.

A succession of tests going back to 2017 have proved blockchain-based bonds can work for benchmark sovereign and supranational issuers; governments; corporates; asset-backed issuers; the new class of “green” bond issues; and even bonds denominated in crypto-currencies.

Only high-yield (or “junk”) bonds have yet to succumb.

So, tokenisation works in the bond markets.

Secondly, tokenisation boosts liquidity in the bond markets.

Bonds – or at least corporate bonds, which are mostly bought and held to maturity – tend to be illiquid, even when monetary policies are not as distorted as they are today.

Tokenisation can fix that.

By breaking bonds into smaller ticket sizes.

Attracting more retail investors.

And by attracting more investors, tokenisation attracts more issuers.

More issuers and more investors means more liquidity.

A number of secondary market trading platforms, such as ADDX and Marketnode in Singapore and SDX in Switzerland, have been set up to exploit exactly that possibility.

Thirdly, bond servicing can be automated.

Bonds are relatively simple, with fixed coupon payments and redemption schedules, so it is easy to write their terms into smart contacts embedded in the bond tokens.

One study estimated that automation of bond servicing by tokenisation would save the global bond markets US$100 billion in securities services fees and another US$100-150 billion in technology maintenance and operating costs.

Fourthly, tokenisation can transform the issuance process.

The primary market in corporate debt issuance is extremely inefficient.

The investment banks which structure and price and syndicate bond issues to other banks and buy-side firms still manage the process by telephone, email, chat rooms, spreadsheets and even faxes.

One FinTech in London found, after running a pilot with a group of major underwriting banks, that blockchain eliminated 93 per cent of the time spent on price indications alone.

The more complex the bonds, the greater the savings.

A study by HSBC of the costs of issuing a US$100 million Green Bond, for example, found they totalled US$6.5 million.

Tokenisation would cut these by nearly 90 per cent, to just $692,000.

Fifthly, what drives liquidity in the bond markets is the repo market, because it is bonds that banks use as collateral to fund themselves and take as collateral to fund others.

So they are always lending and borrowing them in the repo market.

But the repo market is not efficient, and least efficient of all on a global scale.

All over the planet, banks hold enormous buffers of bonds as well as cash at custodians and CSDs, to ensure that they can meet their obligations when they need to.

They have to do that because it is very hard to use a bond in one jurisdiction as collateral for a loan in another.

It is estimated that the excess liquidity held by the Tier One banks is worth €3.65 trillion, and that it costs those banks 0.1 per cent of that sum (€3.65 billion) every year to maintain it.

That obviously provides the banks with a massive financial incentive to find a solution.

Here in Europe, HQLAx, a blockchain-based consortium of banks founded by Clearstream believes tokenisation is that solution.

Tokenisation means the excess inventory held at custodians and CSDs can be used without the bonds ever needing to leave the custodian or the CSD.

Instead, they can move between buyers and sellers with full legal title in a tokenised form across a blockchain network.

In other words, being in the securities business will cost less.

When ISSA asked its members last year to name their blockchain priorities, half of them mentioned repo, and 40 per cent of them were doing something about it.

A recent survey by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) of 21 sovereign, supranational and government agency bond issuers found every single one of them expected the bond markets to be tokenised.

One benchmark issuer, the European Investment Bank (EIB), expects all its €100 billion a year of bond issues to be in tokenised form within five years.

That same ISSA survey found fixed income was the most popular blockchain project among financial market infrastructures.

And when it came to projects that were actually live, securities issuance was top of the list and securities financing and collateral management were not far behind.

Mutual funds are another early candidate for tokenisation.

As you can see on this chart, asset managers and asset owners are even more excited by the idea than the securities services industry.

It makes sense.

Asset management is a business under severe margin pressure.

It needs to cut costs and sell more funds to more investors.

Tokenisation provides a path to doing both of those things.

And funds have properties that make tokenisation appealing.

Too many costly intermediaries.

And a principal-based redemption model.

Fund tokens would instead permit secondary markets in fund shares to develop, allowing investors to sell their holdings rather than redeem them with the asset manager.

In Europe, the big brand asset managers are sufficiently intrigued by the potential cost savings to fund the efforts of fund tokenisation FinTechs in both London (FundAdminChain) and Luxembourg (FundsDLT) already.

In Singapore, alternative fund managers are already using the ADDX exchange to tokenise funds.

Which makes it also an obvious path to follow for any CSD that services funds.

And it does not stop at mutual funds either.

ADDX has reduced ticket sizes in a private equity fund from US$125,000 to US$10,000; in a real estate fund from €1 million to €20,000; and in a hedge fund from US$5 million to US$20,000.

In other words, they are making these hitherto institutional-only asset classes available to retail investors.

It is worth noting that one of the asset classes ADDX is tokenising also happens to be the biggest asset class in the world: the US$326½ trillion real estate market.

Today, CSDs have pretty much none of that.

And they will not get any of it if they rely on the tokenisation of individual buildings.

CSDs are not obviously credible as service providers to tokenised buildings.

Even Deutsche Börse, which has identified real estate tokenisation as major opportunity for 360X, has joined forces with a specialist called Tectrex to issue and trade tokenised securities based on real estate cash flows.

Where every CSD is credible is as a service provider is to real estate funds.

And the growth potential of tokenised real estate funds is massive.

Partly because of the sheer size of the asset class.

And partly because most real estate is owned and managed privately.

Privately managed assets are a market in which tokenisation will almost certainly have a great deal of success.

*

And they are a market which has a particular appeal to CSDs.

Private equity funds are already using CSDs as registrars – what the industry calls, rather grandly, “cap table management.”

But there is an even bigger opportunity for CSDs than that.

Remember those 30,000 companies that have de-listed since 2005.

Where did they all go?

Into private ownership, of course.

Private fund raising has increased every year since the financial crisis of 2007-08 except the year of the global Pandemic – and even then it was pretty healthy.

There is a very simple reason why this is happening.

Institutional money is going private because the returns are higher.

According to McKinsey, the net asset value of private equity funds has grown faster than the market capitalisation of public equities every year since the great financial crisis.

Today, McKinsey estimates the value of assets managed by private equity firms at US$6.3 trillion.

Note also how valuable private debt has become: US$1.1 trillion.

Under the monetary policies that central banks have pursued since 2008-09 it has become extremely difficult for mainstream banks to maintain margins in lending.

Which is why private lending is the only privately managed asset class to have increased its funding every year since 2011.

Privately managed assets as a whole are now worth US$9.8 trillion – nearly twice the size they were just five years ago.

That is a lot of money.

But it is not liquid.

Tokenisation offers a way to make it liquid.

That is precisely the strategy being pursued by the token exchanges.

Is it also a custody opportunity for CSDs?

Yes.

Exchanges do not necessarily protect customer cash deposits.

At best, they will use segregated accounts at independent custodian banks to safekeep uninvested cash.

But they almost all tend to hold tokens on behalf of investors on their private blockchains, from which they cannot be transferred.

Are these arrangements that institutional investors used to independent custody – and to treating their custodian as an insurance policy – will be comfortable with?

Probably not.

If a CSD can persuade investors that it offers a safer alternative to the issuance, settlement and custody of tokens on private or public blockchains, privately managed assets could become a very substantial new source of revenue for CSDs.

The DTCC has already identified privately managed assets as a major new business opportunity.

Its proposed Digital Securities Management (DSM) platform aims to provide an issuance, distribution, trading and settlement platform for privately managed assets in both traditional and tokenised forms.

In effect, DSM will help custodian banks hold tokens on behalf of clients at the CSD just as they hold conventional securities on behalf of clients at the CSD today.

SDX has just announced a similar arrangement with Daura, an equity tokenisation platform for private companies in Switzerland.

Privately managed assets are a clear opportunity for CSDs.

*

Which asset class will tokenise first will vary by country.

If a country has a large real estate sector, or a large mutual fund industry, naturally it should focus its efforts there.

But think also about the obstacles to tokenisation.

There are two big ones.

The first is regulatory.

Issuers want to issue tokens that are fully regulated.

And institutional investors will buy only those tokens that are fully regulated.

Here we confront a paradox.

We know that securities tokens are regulated because security tokens are securities and securities are regulated.

Yet regulatory uncertainty persists.

Why?

Because in common law jurisdictions tokens have yet to be defined by a body of case law.

And in civil law jurisdictions, even those where the government has passed specific token legislation, obligations to comply with other securities market regulations persist.

In both, the regulations that bring the law to life, are not yet completely clear.

In a recent poll, Future of Finance found regulatory uncertainty to be the biggest inhibitor of all.

Both regulated and unregulated entities fear the lack of clarity will cause inadvertent breaches of regulations, leading to regulatory fines.

Until that uncertainty disappears, tokens will struggle to take off.

The second barrier to take-off is a structural one.

This is the lack of fiat currency on token networks.

Securities transactions settle by delivery against cash payment.

And at the moment cash payment has to take place EITHER off the blockchain network.

OR in some ersatz form of cash – a payment token.

The most popular choice at present is the Stablecoin, whose value is (ideally) tied to a holding of the equivalent amount of cash off the chain.

Even before recent events, the fact that this is not always the case was a major inhibitor to institutional use of Stablecoins.

Both the US and UK governments are now bringing Stablecoins within the purview of regulation, so attitudes may change.

But Stablecoins will always be second best to true central bank money.

Which is why many people believe the key to unlocking growth in securities tokens is Central Bank Digital Currencies, or CBDCs.

CBDCs could put central bank money on blockchain networks.

That would drastically reduce settlement risk by making “atomic settlement” possible – albeit by requiring counterparties to maintain higher levels of liquidity (ironically, a problem tokenisation – as HQLAx shows – can alleviate).

Several jurisdictions have issued CBDCs already, and the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) are considering the idea.

The Atlantic Council CBDC Tracker records 80 live CBDC projects around the world.

Settlement of securities transactions has emerged as a major use case for so-called wholesale CBDCs, where the CBDC remains within the banking system.

One major driver for adoption of wholesale CBDCs is the need to cut the cost of settling trades across national borders.

Banks are under pressure from regulators – led by the G20 – to cut the costs and increase the speed and transparency of cross-border payments.

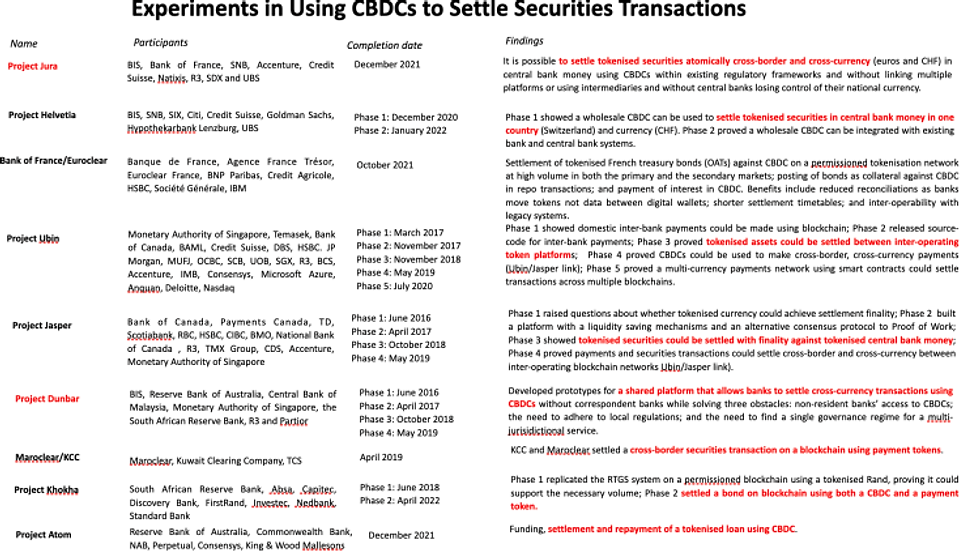

Multiple experiments, in which central banks have led groups of banks and vendors, have now proved that CBDCs can settle securities trades both domestically and across national borders cheaper, faster and more transparently than existing systems.

Project Jura, which closed just before Christmas, has definitively made the case for using CBDCs to cut cross-border settlement costs.

Project Dunbar has proposed a common CBDC platform to make that possible.

This is happening even on the retail side now.

Project Nexus, led by the BIS, wants to link national instant payment systems across borders.

The survival of the correspondent banks looks increasingly improbable.

This has created an opportunity for CSDs to take ownership of the settlement of securities transactions, both at home and across national borders, in central bank money in the form of CBDCs.

But the most important thing about CBDCs is this.

By putting central bank money on to blockchain networks, CBDCs might well turn out to be the spark that ignites the security token markets into a period of dramatic growth.

For CSDs, that means the introduction of a CBDC by one or more of the major central banks should rank as the starting gun for the activation of plans to support the rise of tokenised securities.

*

The question is: what plans?

What should a CSD actually be doing about tokenisation now?

One place to look for guidance is what other exchanges and CSDs are doing.

At ASX, the replacement for its CHESS clearing and settlement system has been delayed four times and may be delayed again.

But in my opinion the most important lesson is not the difficulties with the technology – it is that you cannot make users change their systems – it has to be easy for them to adopt tokenisation technology.

At Clearstream, they have spread their bets: they built a digital CSD and launched ventures in fine art and real estate, but they are also alive to delivering value now, notably in the case of HQLAx, and clearly believe in partnerships – not just in collateral but in funds and real estate too.

DCV in Chile is focusing on fixed income, the biggest asset class in their market and the biggest security market in the world.

But their most important secret is phasing: an incremental approach that contains costs and risks.

DTCC is sticking to its strengths as an infrastructure but in a new asset class – privately managed assets.

Yes, we need to understand why ID2S, the first blockchain-based CSD, failed.

It was certainly not the technology – that worked perfectly.

It was the market, and the regulations, and the incumbents using the regulators to protect themselves.

KDPW is doing something very interesting, to which I will return.

This is to build a blockchain infrastructure, of which the first use-case is proxy voting.

NSD in Russia did a lot of experiments early on.

The real lesson from their work is that technology does not equal liquidity.

STRATE in South Africa also saw value in partnerships – initially with NSD but latterly with Nasdaq.

Of course, many CSDS – including ASX and Clearstream – belong to stock exchange groups.

In fact, stock exchanges are the biggest single group of owners.

Which opens up tokenisation opportunities on the pre-trade and trading sides of the securities industry, as well as the post-trade side

Three Caribbean exchanges – Barbados, Eastern Caribbean and Jamaica – are building integrated tokenisation platforms.

In al three cases, it is part of a wider digitalisation strategy that encompasses a CBDC and, in one case, the Metaverse.

In Jamaica, the CSD has retained control of clearing, settlement and custody.

In Canada, the CSE sees tokenisation as a logical extension of its promise to cut the cost of capital for smaller companies.

Hong Kong is using blockchain to address the Stock Connect settlement timetable mismatch problem.

The most interesting case is the Swiss stock exchange.

Which has built a fully integrated issuance, trading, settlement and custody platform that replicates its traditional exchange, clearing house and CSD.

Wisely, it is offering issuers and investors the choice of using securities or security tokens.

That recognises the transition to a tokenised future will take time and experience.

But the most interesting thing about SDX is why the exchange has made such a large investment.

It is because it figured that the most successful crypto-currency exchanges – such as Coinbase and FTX – had a lot of money; bags of useful experience; and were bound to get regulated and enter the securities industry.

SDX is a defensive move, as well as an offensive one.

And its logic has been proved right.

So far at Future of Finance, we have identified 22 token exchanges which have secured regulatory licences.

Including SDX, which is regulated by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA).

Archax in London is regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

ADDX in Singapore is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

INX in the United State is regulated by both FINRA and the SEC

The SEC recently approved the blockchain-based equity trading platform BSTX as a national securities exchange – which is its highest level of approval for exchanges.

SDX was right to anticipate regulated competition for the securities business.

And CSDs should be monitoring developments on the issuance and trading side extremely closely.

But don’t just look at CSDs and exchanges.

Look at your users too.

The most important of these are the custodian banks.

Five of them are supplying or planning to supply crypto-currency custody services.

Why?

Because their asset owner and asset manager clients want them to.

Note that they are starting with crypto-currency, not security tokens.

And that they are using specialist partners such as Fireblocks and Copper.

It is the classic strategy to buy not build, and to support business which exists now and not at some indeterminate point in a fully tokenised future.

That enables them to contain the cost of their commitment.

Fireblocks and Copper are only two of dozens of specialist crypto-custody service and technology vendors.

At Future of Finance, we have counted more than 80 of them around the world, including not just start-ups but private banks (such as BBVA Switzerland and Mason Private Bank in Liechtenstein) and federally and State chartered banks in the United States (such as Anchorage and Signature).

So the option is there for CSDs to follow the example of the custodian banks and buy the capabilities they need to support tokenised securities.

And it is one every CSD must take seriously.

Because there is a risk that, as these new services grow, the safekeeping and servicing of security tokens will migrate away from the CSDs to the custodian banks, the specialist vendors and indeed the new breed of specialist CSDs such as SDX, Montis and D7.

And that is the first of ten lesson I would like to share with you in closing this presentation.

Do something, or risk being bypassed.

It is extraordinary that token exchanges are building CSDs of their own to develop services CSDs should be supplying.

Secondly, don’t simply copy what others are doing.

Of course it is reassuring to know that other members of the securities services industry are investing in tokenisation PoCs, pilot tests and live services.

It helps to normalise the concept among managers, employees and user-shareholders, and dispel any confusion between tokens and crypto-currencies.

But there is no single or common pattern to the way CSDs, exchanges and custodians are approaching the threat and opportunity of tokenisation.

And that is lesson number two.

Every CSD is unique.

Each inhabits its own jurisdiction; runs operations to comply with specifically local requirements; delivers different services to dissimilar customers peculiar to its own market; and faces its own combination of threats and opportunities in its domestic market.

Don’t simply copy what others are doing.

The third lesson is minimise the impact of change on users.

Users will be reluctant to invest in change if existing systems work well enough.

Don’t make them throw those systems away.

Fourthly, focus on immediate value to users.

Projects likely to deliver immediate value to users are more likely to get their support.

Fifthly, invest incrementally, to contain the risk.

Link your investments in new services to the likely evolution of the market and the length of the transition to a tokenised marketplace.

Sixthly, always choose regulated status – that will bring the institutions in.

Work with regulators and emphasise the regulated status of services.

Seventhly, watch what regulators and central banks do.

Regulators exist to protect retail investors and preserve financial stability.

But at the same time they do not wish to discourage innovations that might increase capital market efficiency and output.

Tokenisation could be just such an innovation.

We have already seen how a CBDC could spark a tokenisation boom.

If the central bank is strongly motivated to issue a CBDC, it is likely to act as a catalyst in the growth of tokenised markets.

Monitoring the progress of a national CBDC is therefore an essential duty of any CSD.

But that’s not all.

If a government introduced a digital identity scheme that too could be a trigger for tokenisation to take off.

Digital identities or the linking of digital assets to digital identities could accelerate the admission of issuers and investors to tokenised networks.

What do the regulators and central banks in your market think?

You need to know.

Eighthly, remember technology is not enough.

Tokenisation needs issuers and investors to provide liquidity.

So invest in non-technology as well as technology, and especially in collaboration with firms that can bring issuers and investors to market.

Which is the ninth lesson.

Collaboration and partnerships are a good idea.

Successful tokenisation initiatives are built not just on technology but mutually reinforcing networks, sometimes sealed with shareholdings, that span regulated market infrastructures, institutional and venture investors, service providers, banks, brokers and FinTechs.

Clearstream, for example, came up with the original idea of HQLAx, but it has chosen not to monopolise it.

Instead, Clearstream has broadened the membership of HQLAx to include BNY Mellon as a triparty agent and agent lender, Goldman Sachs as a principal, BNP Paribas Securities Services as a triparty agent, and Citibank as a custodian.

Also involved are Commerzbank, Credit Suisse, Euroclear, ING and UBS.

To take another example, look at the eco-system that is emerging between SDX in Switzerland, the Japanese investment group SBI Digital Asset Holdings (SBI), the Swiss digital bank Sygnum, Sumitomo Mitsui, the Osaka Digital Exchange (ODX) and the enterprise blockchain company R3.

But it is the tenth and final lesson that is the most important.

And it is this: Be true to your infrastructural character.

What, after all, is an infrastructure?

CSDs are happy to describe themselves and be described as financial market infrastructures without pausing to ask what this means.

A true infrastructure is a common means to many ends.

Infrastructures are trusted, reliable, safe, secure and above all open.

By building a national blockchain infrastructure which others could use to develop token products and services, CSDs could stop waiting for tokenisation to happen and actually do something to unlock the potential of tokenisation.

Examples of blockchain infrastructures exist already.

One is the LACChain Alliance led by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

It provides a secure, open, transparent, zero-fee, public-permissioned blockchain infrastructure for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Alastria, a non-profit established in Spain in October 2017 also runs an open blockchain network infrastructure used by FinTech start-ups.

Likewise, the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI) aims to make it easier for consumers and businesses to access public services across national borders.

KDPW in Poland is going down a similar infrastructural path.

So is DTCC, with its Digital Securities Management (DSM) platform for privately managed assets.

This could be the most valuable contribution CSDs can make: the provision of a national market infrastructure for security tokens just as CSDs today provide a national market infrastructure for securities.

If a CSD can enable securities market participants to take part in tokenised markets without having to rebuild their internal systems, that could rapidly accelerate adoption of tokens.

It would also put CSDs in a position to recruit as clients all the FinTechs which are building applications to support the security token markets.

In fact, as a blockchain infrastructure provider, a CSD could create a new kind of network.

One whose members source components from each other and use them to build new products and services.

One whose members can access digital products and services through a network app.

It is a CSD version of Open Banking or Open Finance.

Openness.

Networking.

These are the right ways to think about how to respond to the challenge which tokenisation sets for CSDs.

If we had had this conversation even two or three months ago, it would have focused on the threat to CSDs rather than the opportunity.

It would have been all about how tokenisation was going to disintermediate CSDs.

Because in principle security tokens on blockchains do not need any of the core services CSDs provide today: issuance, registration, settlement, custody or asset servicing.

The question then was whether CSDs could find a new role for themselves when their old occupation was certain to be gone.

The usual answer was as governing or administering private or permissioned blockchain networks, deciding who could join them, who could not, and punishing wrong-doers.

Well, I think that idea is dead now.

That OMFIF survey I mentioned earlier found that 40 per cent of the sovereign, supranational and government agency bond issuers they asked would be perfectly happy to issue their bonds on to a public blockchain.

Think about that.

The Ethereum protocol that underpins the overwhelming majority of token issues to date is:

– Less than ten years old;

– Controlled by a handful of software engineers;

– Suffers from a chronic inability to process significant volumes of trades; and

– Experiences fluctuations in transaction costs that have varied by a factor of a hundred in the

last five years.

Yet issuers like the EIB and CSDs like the DTCC are now prepared to work with it, not just in experiments, but for real.

The crypto world and the conventional world are converging.

And they are converging because our entire economic way of life is now embarked on a series of seismic shifts that a changing the nature of capitalism.

From a corporate economy to an ownership economy.

From an intermediated economy to a peer-to-peer economy.

From large corporations controlling consumers to consumers controlling large corporations.

From corporate control of data to consumer control of data.

From the Internet plus the Cloud to the Internet plus Blockchain.

From two forms of digital money – commercial bank money and central bank money – to two forms of tokenised money – CBDCs and Stablecoins.

And, last but not least, from securities to tokens.

CSDs have a choice.

They can be crushed by this transformation.

Or they can, by helping to make it happen, join the ranks of those which will gain the most from the transformation.

CSDs could become the operators of the tokenised infrastructure that underpins the networks which knit together every part of the financial services industry in your own country, and links it to every other financial services industry in every other country.

The more I think about it, the less tokenisation feels like the end of the CSD.

And the more it feels like the beginning of an entirely new and more exciting and more profitable future for the CSD.

Tokenised markets need what CSDs can provide: central bank money, customer due diligence checks, safe custody, financing and lending, common infrastructure – above all, inter-operability – the links to other assets, other markets and other countries.

Don’t wait for something to happen to you.

Make it happen, for your owners, your users, and your country.

For further information please contact Wendy Gallagher on wendy.gallagher@futureoffinance.biz